Photo by Chris Bales, 1998 The hues of Space Mountain |

|||

|

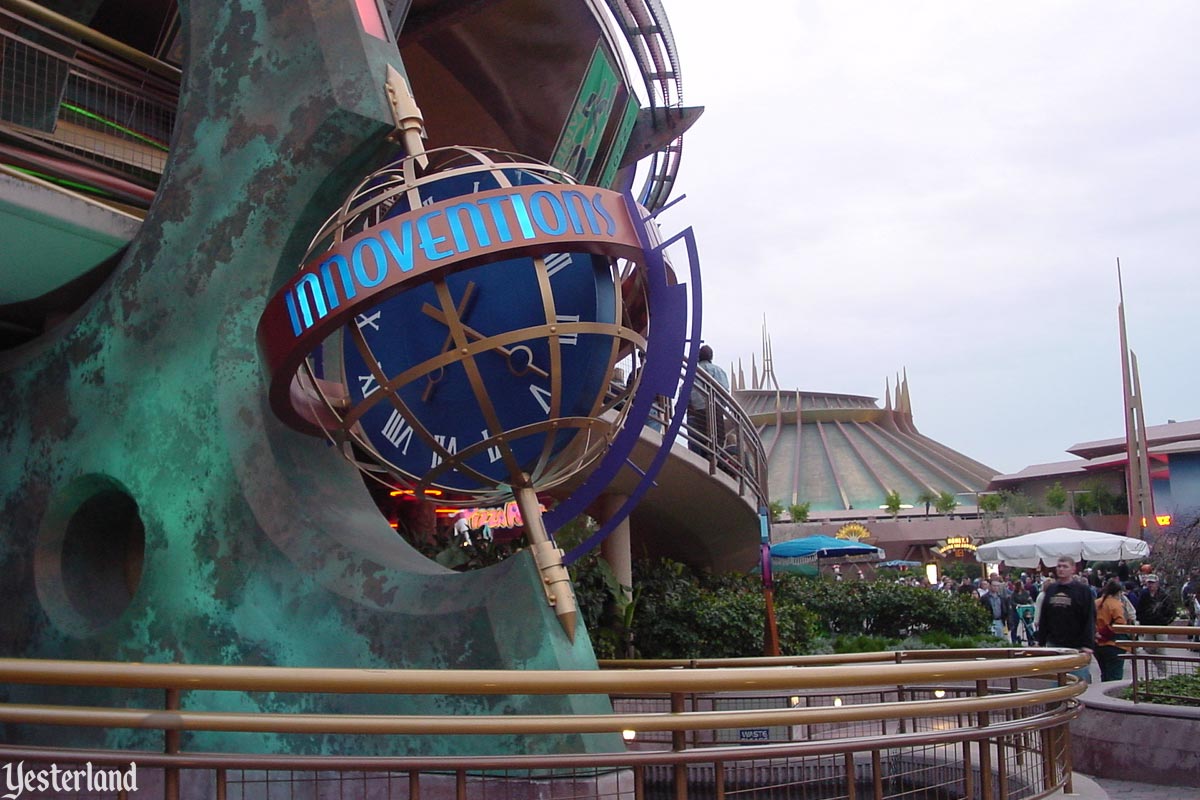

Space Mountain lets you travel through space inside a structure that futurists H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Leonardo da Vinci might have imagined. This giant copper kettle with a green patina represents an ingenious relic from a much earlier era. |

|||

|

|

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2000 Brown Mountain? |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2001 A perfect fit with the rest of Tomorrowland |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2001 Innoventions and Space Mountain with their retro-futurist paint schemes |

|||

Photos by Allen Huffman, 2001 and 2002 Several views of Space Mountain |

|||

|

Pay no attention to anyone who claims that this Space Mountain looks as if it suffered from a massive spill of vomit—or something worse—all over its exterior. Okay, okay. It doesn’t really look like copper or bronze. But pretend that it does. And try to like it. After all, colors like this are all over this version of Disneyland’s Tomorrowland, thanks to the 1998 update. Let’s take a ride! Grab your FASTPASS. Then follow the queue. |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2000 The ride’s logo |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2001

FASTPASS |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2002

Lots of brown |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2000

Original architectural elements, new paint—not all of it brown |

|||

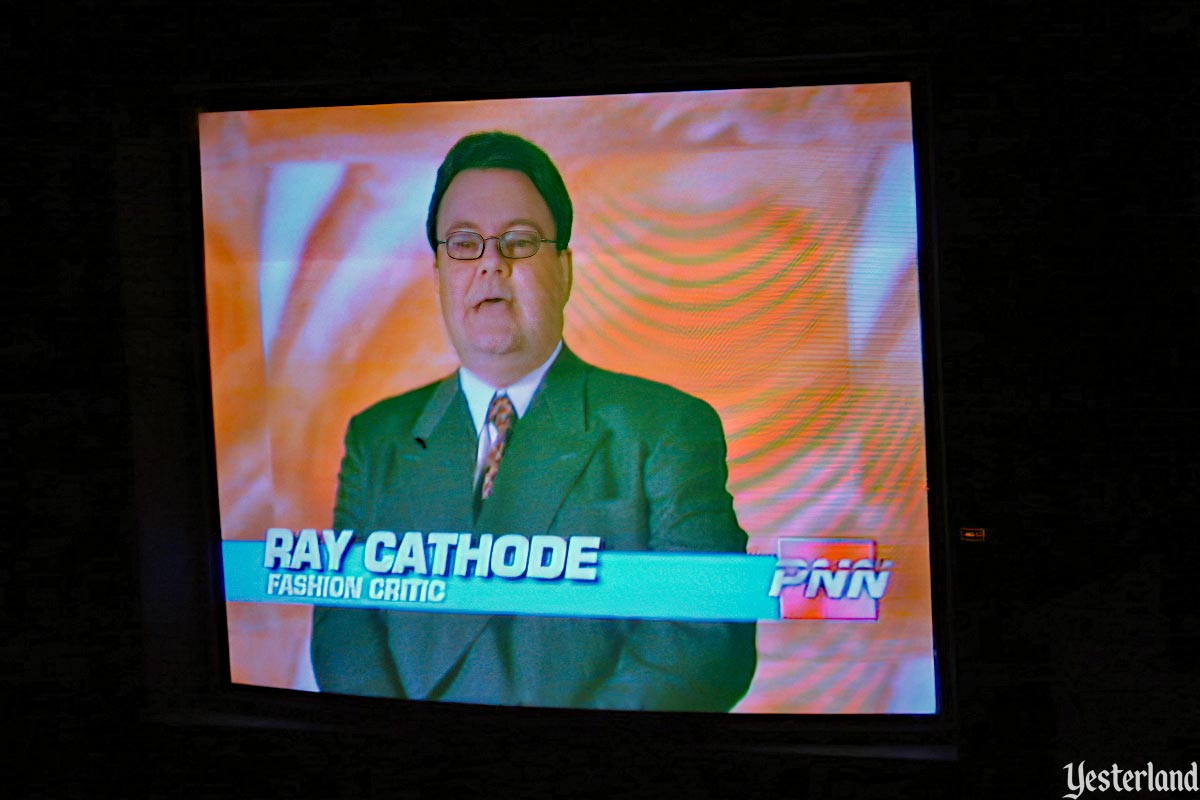

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2000 Ray Cathode of PNN, the Pan-Galactic News Network |

|||

|

Monitors keep you entertained while you wait. In one segment, Ray Cathode (played by Glenn Shadix) tells you, “The hot news at the Mars shows is color.” He’s talking about fashion, not the hues of Space Mountain. |

|||

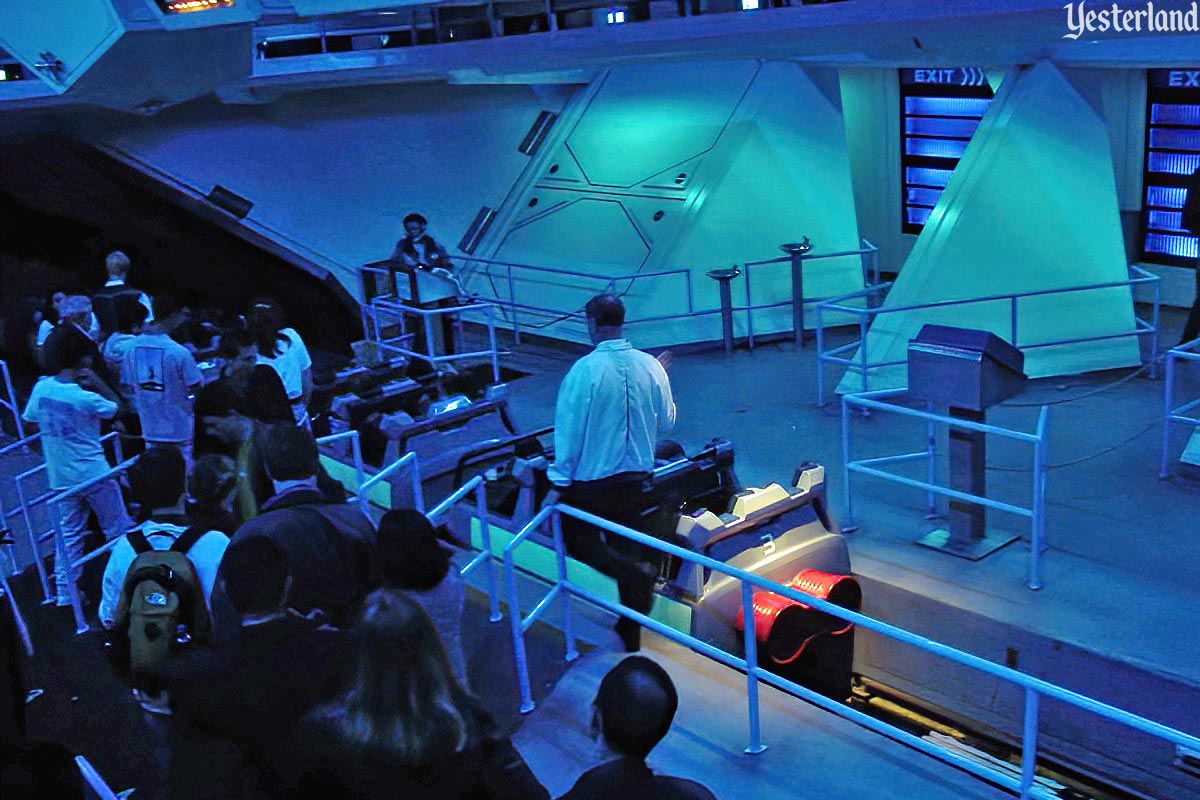

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2001 Loading |

|||

|

When you actually get to the loading area, there’s no indication of the Jules Verne future. Enjoy the ride! |

|||

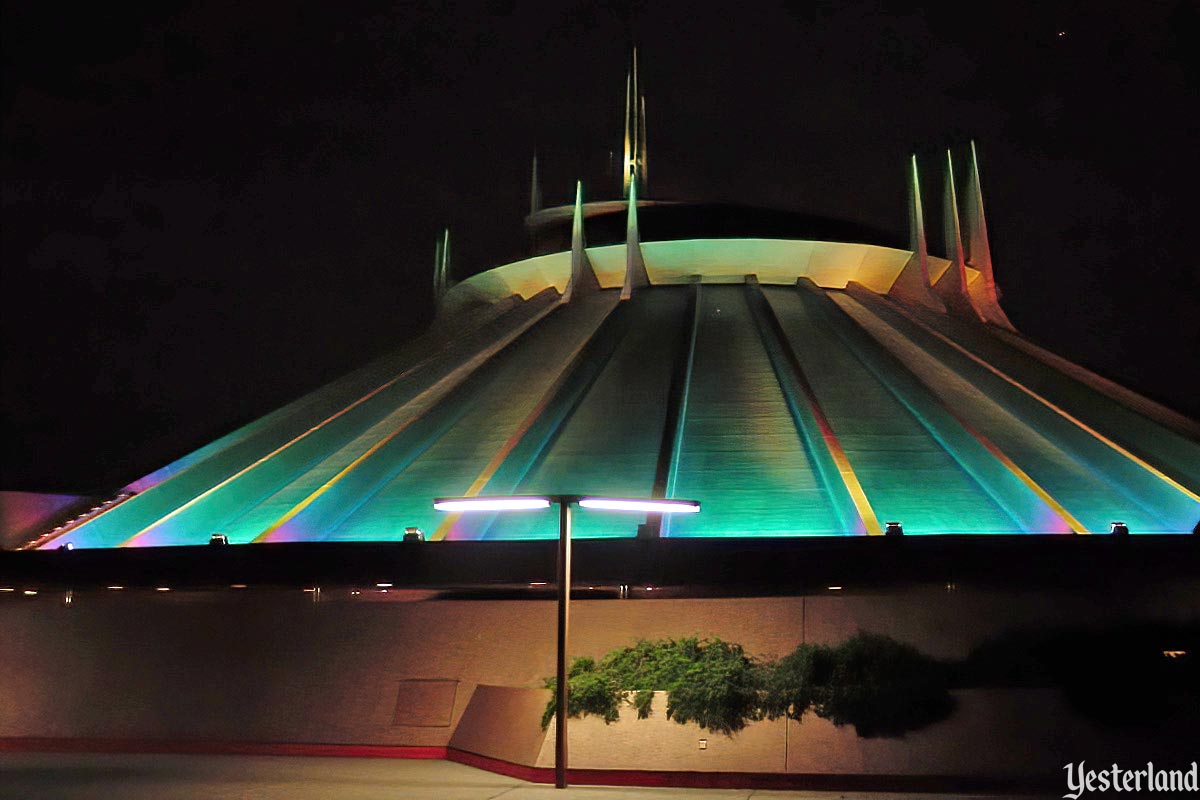

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2001 Night |

|||

|

It looks better at night. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Space Mountain opened at Disneyland in 1977. The indoor roller coaster would be housed in a gleaming white structure for more then 20 years. Space Mountain had been designed to fit into the New Tomorrowland of 1967—which had replaced the original Tomorrowland just 12 years after the opening of the park. |

|||

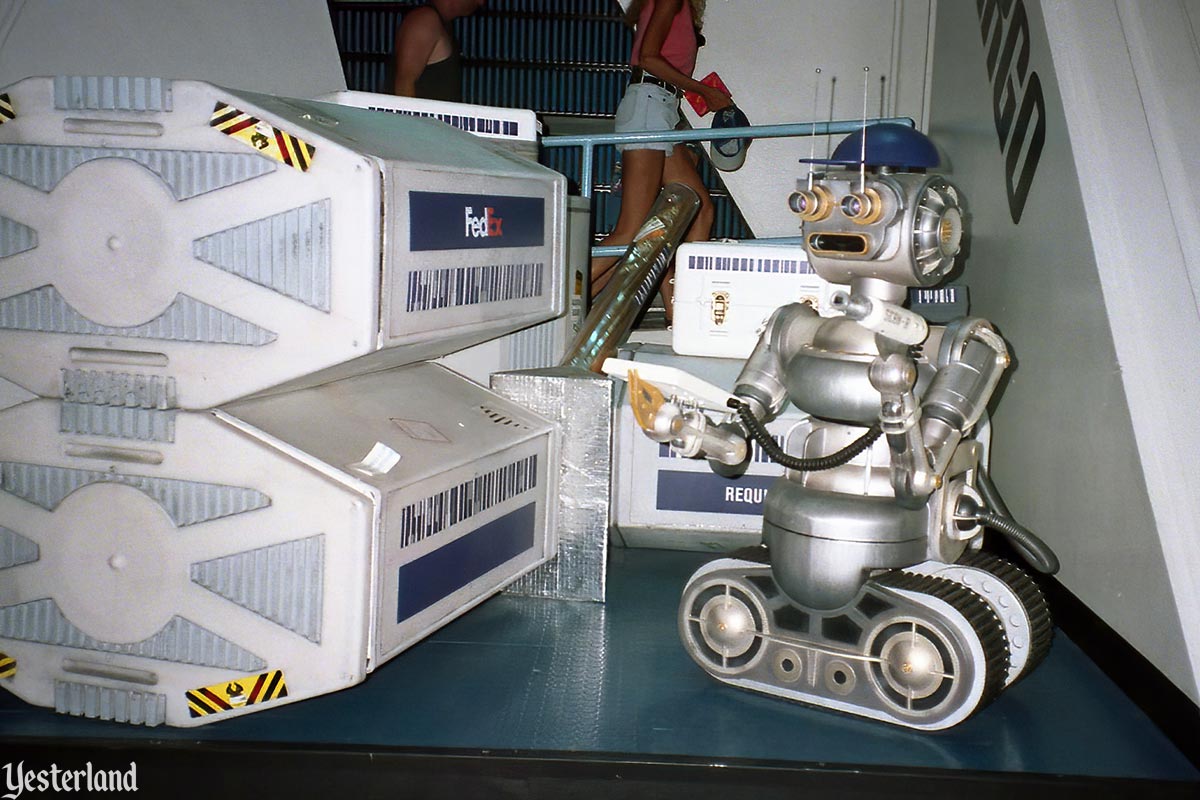

Photo by Chris Bales, 1995 FedEx in Disneyland’s Space Mountain, 1995 |

|||

|

In 1995, Federal Express (FedEx) became the sponsor of Space Mountain, a relationship that would last ten years. With the sponsorship came a more entertaining queue and new displays. In 1998, the exterior of Space Mountain was given a brownish, greenish, copperish paint job as part of a new New Tomorrowland project. It must have seemed like a good idea at the time. It had been 31 years since the last New Tomorrowland—and this “World of Tomorrow” was anything but futuristic. To make matters worse, America Sings (1974) had been silenced in 1988 and Mission to Mars (1975) was decommissioned in November 1992, leaving two highly visible attraction buildings behind. |

|||

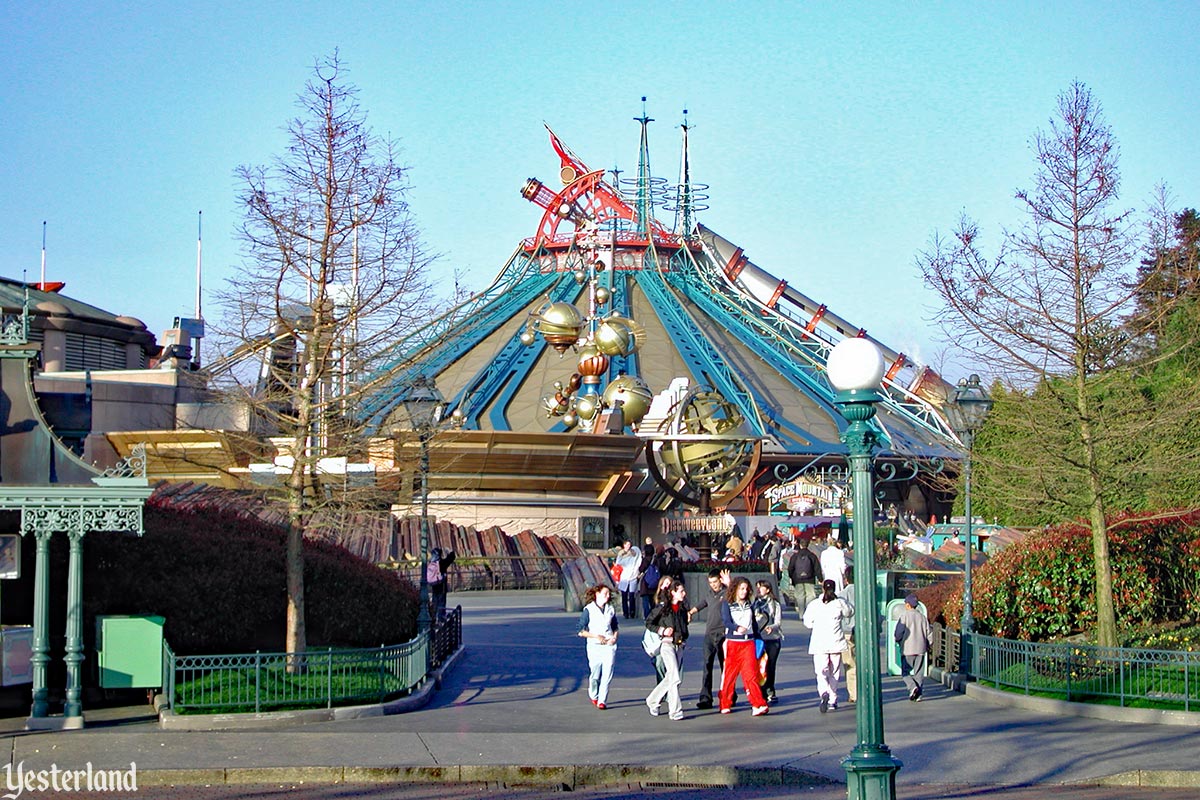

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2005 Space Mountain, which opened in 1995 at Discoveryland, Disneyland Paris |

|||

|

The executives in charge of Disney’s theme parks learned important lessons from Disneyland Paris, which had opened in 1992 as Euro Disney. One of these was that a retro-future theme solves the problem of trying to stay ahead of the actual future. Another was that capital spending needs to be kept under control to avoid the red ink that plagued the Parisian park. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2001 Load area at Disneyland Paris, carrying the exterior theme into the interior |

|||

|

While Disneyland Paris had retro-future architecture, the original Disneyland would try to accomplish the same thing primarily with paint. Disneyland would get a retro Tomorrowland on a tight budget. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2000 The bronze hues of Disneyland’s Tomorrowland in 2000 |

|||

|

The Los Angeles Daily News (“Back to the Future; Disney Revises Tomorrowland,” by Dave McNary, May 19, 1998) decribed Disneyland’s approach like this: Disneyland has abandoned the idea of predicting the future in favor of bringing to life the dreamlike visions of Leonardo da Vinci and Jules Verne. So the stark, sleek look is gone, replaced by golds, browns and cobblestone walkways. The Wall Street Journal (“A new Tomorrowland dawns; What does the future look like now?” by K.E. Grubbs Jr., May 29, 1998) took it a step further, with an observation about the effect of this change: But the new Tomorrowland is not really earth-bound. Like the old version, it spends a great deal of time sending its visitors into space. And here the design scheme is now much less the Jetsons-style sleekness of the old Tomorrowland and oddly more retro. Space Mountain, a roller coaster meant to give the sensation of hurtling through space, remains, but its tall exterior is repainted, curiously, to look like greenish, oxidizing copper. The intention: earth-friendly. The effect: grunge. The grunge look did not suit Space Mountain. |

|||

Photo by Allen Huffman, 2004 Gleaming white Space Mountain in the brown Tomorrowland |

|||

|

In 2003, Space Mountain was restored to its original white color. The rest of Tomorrowland followed with a new palette of silver, grays, and blues. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2013 Space Mountain in 2013 |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2013 Space Mountain sign in 2013 |

|||

Photo by Chris Bales, 2022 Star Wars-themed Hyperpace Mountain in 2022 |

|||

|

By now, it’s hard to remember that Space Mountain was ever a color other than white. |

|||

|

|

Click here to post comments at MiceChat about this article.

© 2022 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated August 5, 2022 |

||