|  |

|

Book Review

The Disneyland Encyclopedia

The Unofficial, Unauthorized, and Unprecedented History of Every Land, Attraction, Restaurant, Shop, and Event in the Original Magic Kingdom

Author:

Chris Strodder

Santa Monica

Press, 2008

Reviewed

by

Werner Weiss

June 12, 2008

|

“As a Disneyland fan, this is the book I always wanted to read but never found.”

— Chris Strodder, author of The Disneyland Encyclopedia

|

|

|

This is a review of the 2008 edition of The Disneyland Encyclopedia.

Yesterland also has a review of the Updated Third Edition (2017).

|

|

Yikes!

This might be the longest book title I’ve ever seen:

The Disneyland Encyclopedia: The Unofficial, Unauthorized, and Unprecedented History of Every Land, Attraction, Restaurant, Shop, and Event in the Original Magic Kingdom. (Well, technically everything after the colon is really just a subtitle.)

Does this book really cover “every land, attraction, restaurant, shop, and event” as the subtitle claims?

Five hundred is a large number, but for a park that has continually changed over a period of almost 53 years, are there really enough entries to fulfill the promise on the cover?

|

An example of a map by Tristan Tang

|

Before I answer that question, I should describe the book.

As the book’s title suggests, author Chris Strodder chose to organize the material using an A-to-Z encyclopedia approach.

Within the 6-inch by 9-inch quality paperback book, there are 480 pages with 500 entries, 350 photos, 50 sidebars with various lists, maps of each “land” created for the book by artist Tristan Tang, an appendix that categorizes the book’s entries, a bibliography, and an extensive index.

When I first opened the book, I randomly opened it to entries such as “Dalmatian Celebration,” “Oaks Tavern,” and “Upjohn Pharmacy.”

As I jumped around the book, the entries were interesting, well-written, and accurate.

|

|

Other Disneyland park histories have used a chronological approach or a geographical system (by “land”).

Each system has its advantages and flaws.

The advantage of the encyclopedia format is that it should be easy to look up any attraction, store, or restaurant by name.

A single entry can deal with changes over many decades.

The disadvantage is that related attractions, shops, and events can be at opposite ends of the book; that’s where the appendix is useful.

|

|

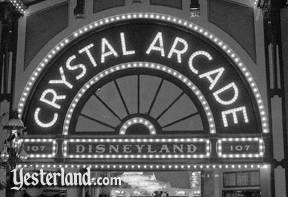

If you’re looking for historic images or stunning color photos, you won’t find them in this book; that’s not its mission.

The photos are fairly small, black-and-white photos taken in 2007.

They illustrate the entries appropriately, and they add to the readability of the book.

The images in this book review are examples of photos from the book, provided to me by Chris Strodder (although I’ve used color versions in some cases).

|

|

|

In addition to the entries for attractions, shops, and eateries, there are also short biographies of dozens of people who were pioneers in the development of Disneyland or who entertained there.

|

|

So, now let’s get back to my question.

Is the book really as comprehensive as the cover boldly claims?

Right off the bat, it was clear to me that this book is more comprehensive than my Yesterland website.

But I’ve never claimed that Yesterland includes everything that’s gone from Disneyland.

Although the book’s claim is really an impossible standard to achieve, I wanted to see how close Strodder got.

My test would not be exhaustive. And I would not look for insignificant omissions.

|

|

To test the book’s claim, I made a list of ten things I expected to find in it as encyclopedia entries:

- Babes in Toyland Exhibit (1961-1963), a walkthrough attraction in the Main Street Opera House;

- Baloo’s Dressing Room (1991), a character meet-and-greet in Fantasyland;

- Flights of Fantasy Parade (1983-1984), a parade that replaced the Main Street Electrical Parade for two summers;

- Flight Circle (1955-1966), a demonstration area for gas-powered model airplanes, cars, and boats in Tomorrowland;

- Intimate Apparel Shop (1955-1966), on Main Street, U.S.A., home to the Wizard of Bras;

- Jolly Trolley (1993-present, but no longer operating), a former ride in Mickey’s ToonTown that’s now just a photo opportunity;

- Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland (1960-1977), a major ride in Frontierland;

- Mineral Hall (1956-1962), a rock exhibit and shop in Frontierland;

- Show Me America (1970), a stage show in Tomorrowland, promoted as Disneyland’s big attraction for summer 1970;

- Welch’s Grape Juice Bar (1955-early 1980s), a beverage and frozen dessert counter in Fantasyland.

|

|

I immediately found the entries for items 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, and 10.

So what happened to the other three?

At this point, I realized that the book makes no claims regarding shows or parades.

They’re not ignored entirely, but Strodder is far more interested in obscure shops than in major shows and parades.

|

|

|

I checked the index for the Flights of Fantasy Parade.

Nothing—not even an index entry pointing to a mention of it anywhere in the Disneyland Encyclopedia.

As I proceeded to read other parts of the book, I actually found Flights of Fantasy mentioned twice.

The Main Street Electrical Parade entry says, “In 1975 and ’76, a special America on Parade celebration commemorated the Bicentennial, and in ’83 and ’84, the Flights of Fantasy parade took over Main Street to coincide with the Summer Olympics.”

Another entry simply called “Parades” includes a chronological list of 38 Disneyland parades, including “1983 - Flights of Fantasy Parade.”

Still, it’s puzzling that it was omitted from the index.

|

|

In contrast, Show Me America has an index entry.

It points to an entry about the Tomorrowland Stage, which includes this description:

Among the large-scale musical spectaculars presented here on Sunday nights were Show Me America and Country Music Jubilee; the book Disneyland: The First Quarter Century describes the former as “a past-paced musical comedy” with “more than 120 sparkling costumes” and “favorite American melodies sprinkled with a touch of old-fashioned humors,” eventually playing 124 performances “acclaimed by audiences and critics alike.”

By the way, Show Me America was actually presented Monday through Friday, twice nightly, in 1970, while the Country Music Jubilee featured name acts on Sunday evenings.

|

|

|

That left the Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland—a major “E” ticket attraction in its heyday—as the last of the three missing items.

Even though there was no alphabetic entry for it (or for Mine Train Ride as it was called in many Disneyland Guide booklets of the 1960s and 1970s), it had to be in the index, right?

Wrong.

|

|

So I looked for Rainbow Caverns Mine Ride, the park’s original mine train ride.

I found it.

It turned out that the entry included both the 1956 version of the ride and the greatly enhanced 1960 version—which it called the “Western Mine Train Through Nature’s Wonderland (sometimes simplified without the ‘Western’).”

There was a time when Disneyland did not make an effort to be consistent when it came to attraction names.

But it was unusual to see this ride’s name begin with “Western” (although the 1961 Disneyland souvenir guide calls it the “Western Mine Train,” and undoubtedly so do other souvenir guides.)

In any case, a reader should have been able to find it in the index by looking for the more common name or even simply for “Mine Train.”

Although the index is large and initially appears to be very complete, there’s room for improvement.

|

|

I would consider Disneyland’s Mine Train rides from 1956 and 1960 to be two distinctly different attractions with different names, different track layouts, and largely different scenery—and thus worthy of two distinct entries.

However, Strodder prefers to offer a single entry so that he can better discuss how attractions evolved over the years.

That’s a legitimate and reasonable approach, but sometimes it buries attractions that one would expect to find easily in the book.

By the way, this is one of the ways that the book is able to be so complete with just 500 entries.

|

|

Tomorrowland has had three distinctly different rocket-themed spinner rides—the Astro-Jets aka Tomorrowland Jets (1956-1966) on ground level near the back of the land, the Rocket Jets (1967-1997) on a base high above the PeopleMover platform, and the Astro Orbitor (1998-present) at ground level near the entrance to the land.

Strodder has combined the first two in one entry, while the third has its own entry.

I’m not sure I follow the logic.

Along the same lines, Rocket to the Moon (1955-1966) and Flight to the Moon (1967-1975) are combined in a single entry, even though the latter was in a brand new building with an Audio-Animatronic “Mission Control” pre-show, higher-capacity theaters, and seat bottoms synchronized to the presentation.

But Mission to Mars (1975-1992), a relatively minor update to Flight to the Moon, has its own entry.

|

|

|

Although the book tries hard to be accurate, it isn’t perfect.

For example, the entry about the Jolly Trolley seems to suggest that the ride is still wiggling through Mickey’s ToonTown.

In fact, all that remains of it today is an unused track and a single vehicle parked at the station—and chained down.

So far in this book review, I’ve identified several problems.

But that doesn’t mean I don’t like the book.

In fact, I really like it, despite its imperfections.

This book is clearly a labor of love by an author who admires Disneyland, knows Disneyland, has personally watched the park change over the years, and has dug up all sorts of facts and trivia from period resources.

Strodder begins the book’s introduction with these two paragraphs:

Writers are frequently asked how long it took them to write their works. Technically I wrote this one in about a year, from the summer of 2006 to the summer of 2007. But in truth, I’ve been working on it for over 40 years, dating back to the very first time I walked with my parents, brother and sister into Disneyland one hot summer’s day in the 1960s.

Like most impressionable kids making their first pilgrimage to a park on the scale of the Magic Kingdom, I was overcome with sensations. There was simply too much to comprehend, too many sights and sounds to take in. Dazzled and dizzy, I came away with a swirl of overlapping memories, a T-shirt splattered like a Jackson Pollack painting, and my first Disneyland souvenir book. As soon as we got home I read everything I could turn up about the park in our Northern California libraries, and I began to keep my eyes peeled for all the Disneyland-related TV specials I could tune in on our old rabbity-eared black-and-white TV. I was just a kid, but my encyclopedia research had begun, though I didn’t know it at the time.

|

|

There are several ways to enjoy this book:

- You can read it cover-to-cover, especially if you’re the type of person who likes to approach things in a systematic way.

- You can jump around in it, reading a few entries at a time in no particular order (perhaps the perfect bathroom book for a Disneyland fan).

- You can take it with you to Disneyland and give yourself and those who are with you on-the-spot Disneyland history lessons.

From this review, I’m sure you’ve figured out that The Disneyland Encyclopedia is not a “how to visit Disneyland” travel guide.

Yet this book could be very interesting even for first-time Disneyland guests, if they’re the type of people who like to approach new experiences with historical perspective.

|

|

The ultimate question that a book review should answer is, “Is this book worth buying?”

If you enjoy Yesterland, and you’d like to read about hundreds of obscure and well-known Disneyland attractions, shops, restaurants, people, and events, the answer is yes.

If you’re old enough to remember past decades at Disneyland, the book will jog your memories.

Many of the entries in this book will probably never be included within the Yesterland website.

If you’re young, you’ll gain insight about Disneyland’s past.

The book is relatively inexpensive because it’s not a fancy art book, although it’s printed on good paper.

If you already have an extensive library of actual period guide books or more recent books about Disneyland’s history, you will already be aware of much that’s in The Disneyland Encyclopedia.

Even so, it’s good to have so much collected in a single book.

|

|

About the Author: (from the book)

The Disneyland Encyclopedia is Chris Strodder’s seventh book, the sixth published since the year 2000.

Several of his books before this one have some connection to Disneyland: Lockerboy, an adventure novel published in 2002 by Red Hen Press, uses an invented Disneyland-like park as a major setting; The Encyclopedia of Sixties

Cool, a nonfiction compendium published in 2006 by Santa Monica Press, includes text about Disneyland in the 1960s.

Among Chris’s other works are the children’s book A Sky for Henry, the comic novel The Wish Book, the short story collection Stories Light and Dark, and the popular nonfiction book Swingin’

Chicks of the ’60s, which garnered international attention, coverage in dozens of magazines ranging from the National Enquirer to Playboy, and exposure on national TV and radio shows.

Chris lives in the green hills of Marin County, California.

|

|

© 2008-2017 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks

Last updated April 5, 2017.

The Disneyland Encyclopedia book cover, photographs, and map: © 2008 Chris Strodder.

Photos by Chris Strodder, used with permission from Chris Strodder.

Map of New Orleans Square by Tristan Tang, used with permission from Chris Strodder.

|

|