|

Why Did the Disneyland Hotel Have Erector Set Architecture? |

||

|

|

|||

|

This story has largely disappeared because the subject of the story no longer exists. It’s still a good myth. And it’s a good excuse to publish some cool vintage photos.

|

|||

|

The Claim: The Disneyland Hotel had erector set architecture because its owner also owned the company that made erector sets. Status: False |

|||

|

|

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Erector set theme? |

|||

|

As with many myths, there are elements of the claim that are true. There was a time when Wrather Corporation owned both the Disneyland Hotel and the A.C. Gilbert Company, maker of the Gilbert Erector Set. However, the original design of the Disneyland Hotel in 1955 had nothing to do with the Gilbert Erector Set. Don Ballard, author of Disneyland Hotel: The Early Years 1954-1988, explained why the two are not related: Jack Wrather did (eventually) own the A.C. Gilbert Company. Wrather acquired it in December 1961, but the Disneyland Hotel was built in 1955. The architectural plans using the ornamental steel girders were by architects Pereira & Luckman back in late 1954 and early 1955—some seven years prior to Wrather buying Gilbert. The company responsible for the build of the girders was Atlas Ornamental Ironworks under the direction of contractors Hodges & Vandegrift, using the Pereira & Luckman designs. I believe to a large part these girders were inspired by the times reflecting Space Age design and motif. |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Restaurants by Gourmet |

|||

|

When Walt Disney began building Disneyland back in 1954, he saw an opportunity for a hotel adjacent to the park. But Disneyland Inc. lacked the financial resources. The solution was to search for a hotel operator with the resources and—more importantly—the willingness to risk millions of dollars building a hotel that would fail if the park failed. The contract went to Jack Wrather, the Texas oil man who had become a movie producer, television producer, broadcast station owner, and operator of two small resorts. Wrather-Alvarez Hotels, a business partnership with television broadcast pioneer Helen Alvarez, successfully lined up investors. (A few years later, Wrather would buy out Alvarez’s interest.) |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Construction of guest rooms |

|||

|

In January 1955, Disneyland Inc. announced the Disneyland Hotel. It would cost $10 million and would be “the largest hotel and motor hotel built in California since before World War II,” The design was by the Los Angeles architectural firm of Pereira & Luckman, whose recent work had included Robinson’s department store in Pasadena (1951), CBS Television City in Los Angeles (1953), and an impressive list of other major projects. The first phase of the Disneyland Hotel opened October 5, 1955. |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Before and after the Monorail extension |

|||

|

The hotel was sleek and contemporary. Its most distinctive architectural feature was the use of steel columns topped by a network of steel beams with hexagonal holes. This framework did not support a roof or have any other structural significance (except to support a few signs that did not require such a structure). There’s a term for I-beams with hexagonal holes: castellated beams. Such beams have been used in construction for their structural strength since the early 1900s. You might think that the hexagonal holes would weaken them. Actually, they’re stronger than solid I-beams of the same weight and amount of material because the “I” is taller. The added bonus is that the holes accommodate pipes and conduit. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2011 LEGO Kingdoms at LEGOLAND Florida |

|||

|

The adjective castellated normally describes the pattern of cutouts at the top of castle walls. Castellated beams are manufactured in two lengthwise halves. Each half has cutouts with a pattern somewhat like the top of a castle wall (except the sides are angled instead of perpendicular. When the two halves are welded together, the cutouts become hexagons. At the Disneyland Hotel, the beams provided visual interest at a time when many architects were moving away from traditional architectural elements. A traditional hotel might have had neoclassical columns with ornate capitals, but the Disneyland Hotel had its sculptural steel framework. Pereira & Luckman apparently found the appearance of the castellated beams more interesting than solid I-beams and used this standard construction material in a nonstandard way. |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Jack and Bonita Wrather |

|||

|

Sam Gennawey—urban planner, MiceChat blogger, and author of Walt and the Promise of Progress City—explained the architecture of the Disneyland Hotel in the context of Mid-Century architectural trends: In 1922, architect Phillip Johnson documented this then-new style of architecture that looks at volume rather than mass. He called this the International Style and the idea was to create a form of architecture that could feel at home everywhere. Johnson said the form of the building would be driven by “regularity rather than axial symmetry.” The smooth surface of the windows captures the sky and the asymmetrical setbacks animate the image. As Johnson stated, the design places “emphasis upon volume—space enclosed by thin planes or surfaces as opposed to the suggestion of mass and solidity.” The Disneyland Hotel’s design shows a collection of buildings that demonstrates “regularity as opposed to symmetry or other kinds of obvious balance.” The facility’s beauty is enhanced “upon the intrinsic elegance of materials, technical perfection, and fine proportions, as opposed to applied ornament.” It makes sense. The sculptural framework at the Disneyland Hotel defined volume, but essentially no mass. |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard Jack Wrather and A.C. Gilbert Jr. |

|||

|

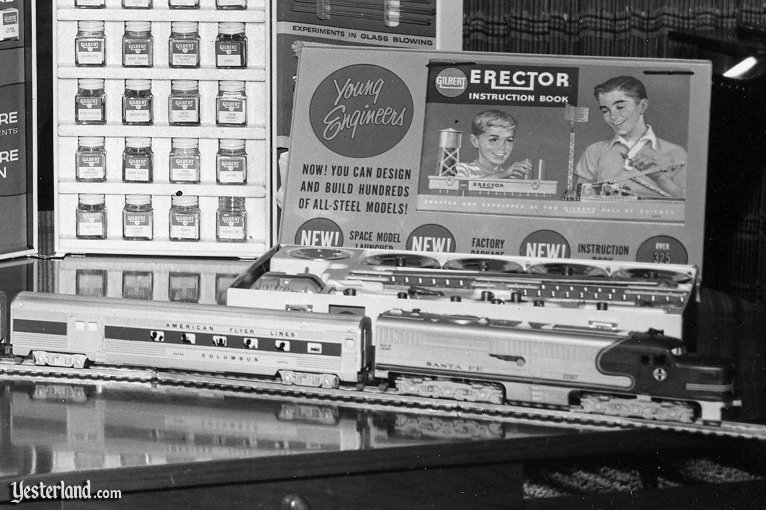

Fast forward to December 1961. A.C Gilbert Jr. and Jack Wrather announced that Wrather Corporation had agreed to purchase the Gilbert family’s common stock in the A.C. Gilbert Company. Erector set inventor A.C Gilbert Sr. had died in January of that year. Holding a 51% stake, Wrather owned control of the toy company. The A.C. Gilbert Company may seem like an odd fit for a company that made television programs and owned the Disneyland Hotel—until you consider that Wrather also owned Muzak Corp. and boat builder Stephens Marine. Wrather was a mogul and entrepreneur who did not limit himself. In 1964, A.C. Gilbert Jr. also died. Jack Wrather took on the role of president and chief executive officer of the A.C Gilbert Company. Shops at the Disneyland Hotel put A.C. Gilbert Erector Sets and other Gilbert products on their toy shelves. |

|||

From the collection of Donald Ballard A.C. Gilbert toys |

|||

|

A.C. Gilbert turned out to be a bad investment. An article in the New York Times (“Deep in the Heart of Texas, ‘Real-World’ M.B.A.’s: Millionaire Dean Pulls B-School To Nation’s Forefront” by Marylin Binder. April 25, 1971) quoted Jack Wrather sharing his experience with graduate students at the University of Texas: “You learn from the mistakes you make,” said Mr. Wrather who describes himself, according to the custom in these parts, as “a country boy from East Texas.” “We bought a company, A.C. Gilbert, that looked like a bird’s nest on the ground, but when it went down we took a $10-million bath on it,” he said, and then told how he had managed that disaster. As Jack Wrather expanded his hotel’s shopping, dining, and meeting room options over the years, many of the beams disappeared inside these new additions. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 1996 Remanants of the “erector set” framework at the Disneyland Hotel in 1996 |

|||

|

Jack Wrather died of cancer on November 12, 1984, at age 66. In 1988, The Walt Disney Company acquired the Disneyland Hotel. In 1999, Disney demolished the older parts of the Disneyland Hotel to make way for Downtown Disney. Even in the final years of the original Disneyland Hotel buildings before their demolition, some of the distinctive beams with hexagonal holes remained in view. But afterwards, the distinctive beams with their hexagonal holes were history. |

|||

Photo © Disney Castellated beam at the Disneyland Hotel Monorail Pool |

|||

|

The Disneyland Hotel received its largest renovation ever in 2011. Reflecting its name, the hotel finally had a real theme—Disneyland. The highlight of the renovation was a pool slide that paid tribute to the original Monorail Red and Monorail Blue from 1959. There’s another tribute on the pool slide. Yes. It’s a steel beam with hexagonal holes. |

|||

|

|

|

||

|

Thank you to author Don Ballard for most of the photos in this article. |

|||

|

Courtesy of Donald Ballard Disneyland Hotel 1954-1959: The Little Motel in the Middle of the Orange Grove |

||

|

For more about this book, including ordering information—or just to enjoy historical photos of the Disneyland Hotel online—visit www.Magicalhotel.com. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

© 2012 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated September 21, 2012. Some photos from the collection of Donald Ballard are courtesy of the Wrather family and/or the Wrather Archives at Loyola Marymount University, courtesy of Chris Wrather and the family of Jack Wrather, with thanks to Don Ballard. Some images may originally have been copyright Wrather Corporation, which was acquired by The Walt Disney Company. |

||