|

|||

Photo by Charles R. Lympany, circa 1956, courtesy of Chris Taylor |

|||

|

Orange County historian Chris Jepsen did some amazing research into the authentic San Francisco Cable Cars that operated at Knott’s Berry Farm from 1955 to 1979, including how they got there and what happened to them. Enjoy this detailed article and the accompanying vintage photos.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

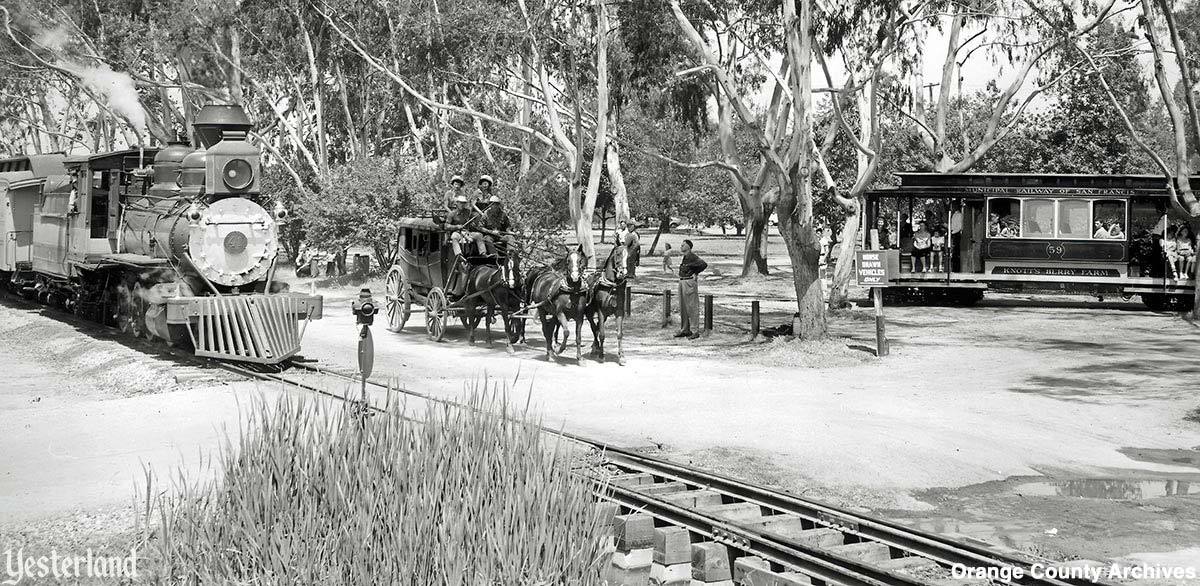

In the morning fog, the uniformed gripman rang his bell, brought the old cable car to a stop, and let another group of happy tourists climb aboard a rolling piece of California history. Where? Why, Buena Park, of course! |

|||

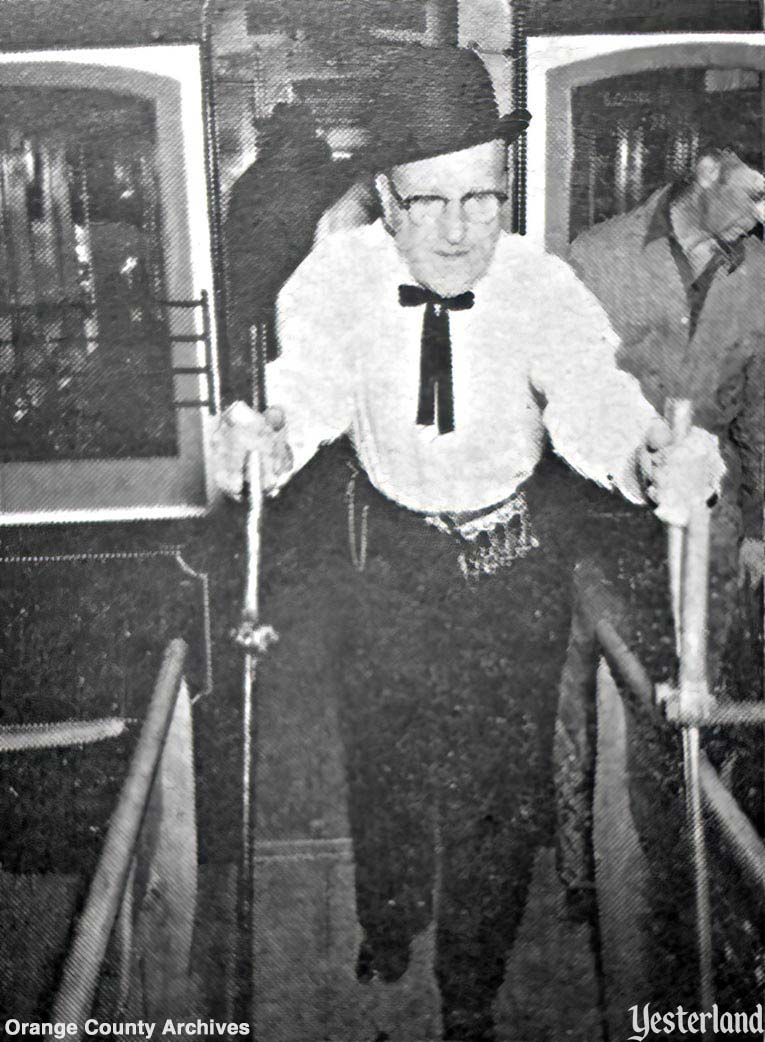

Photo, 1964, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Dress for the occasion |

|||

|

For more than two decades, Knott’s Berry Farm was home to six genuine San Francisco Cable Cars, at a time when that transportation system was temporarily on the wane in the “City by the Bay.” On March 8, 1955, Virginia Knott Reafsnyder — daughter of Knott’s Berry Farm founders Walter and Cordelia Knott — and her husband Ken Reafsnyder were among about 300 bidders at a Bay Area auction, hoping to win some of the ten cable cars being sold by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. The City’s longtime surplus equipment manager James E. “Big Jim” Leary arranged the sale. Ultimately, the Reafsnyders won four California Street Cable Cars (numbers 6, 17, 20 and 59) for a total of $8,838.90. At least three of these cars, including #6 and #20, had been built in 1906 by J. Hammond & Co to replace stock destroyed on the California Street line by the great 1906 earthquake. The Knotts felt that bringing the cars to their farm fit perfectly with their mission of sharing the history of the West. Indeed it did. But there were also other reasons to buy the cable cars. Naturally, the cars would be one more attraction for visitors to enjoy. More importantly, the Knotts were watching the development of Disneyland, less than seven miles away, and knew of Disney’s plan to use motorized trams to bring guests from every corner of their massive parking lot to their front gate. It was an idea worth borrowing. Knott’s had numerous huge parking lots of their own, and a short-lived attempt at using a low-capacity jitney had been unsatisfactory. The cable cars were an ideal solution that also happened to have rich historical provenance. |

|||

Photo, 1955, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Arrival of Cable Car number 49 at Knott’s |

|||

Photo, circa 1955, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Rebuilding San Francisco Cable Cars at Knott’s |

|||

|

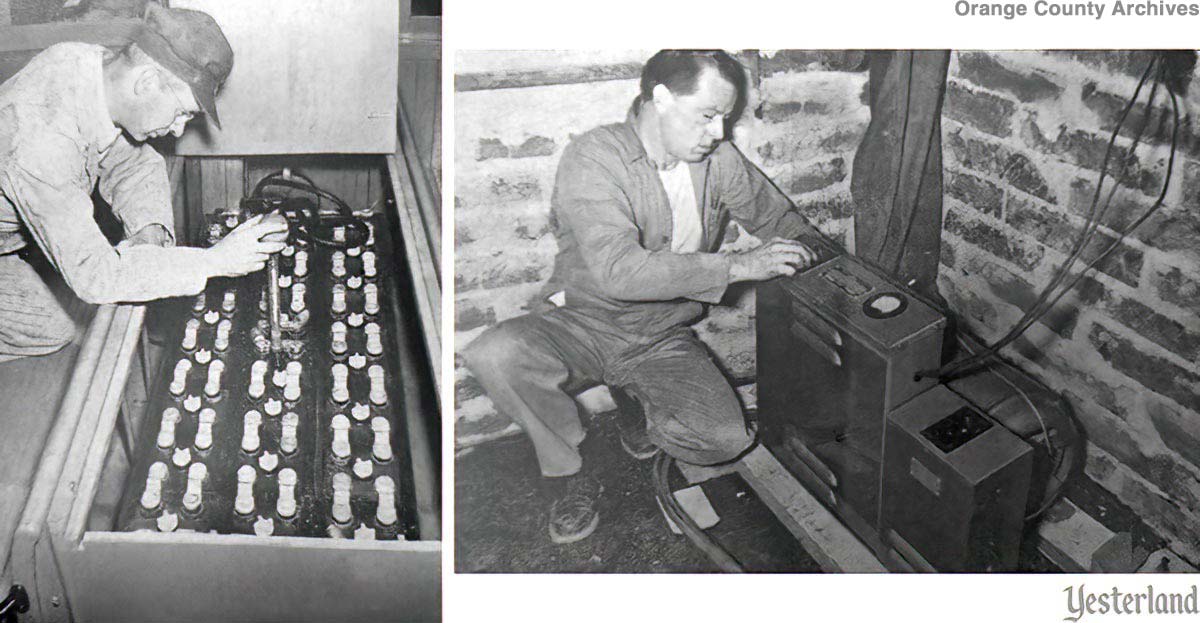

Immediately upon word of the cars’ purchase, the railroad crew at Knott’s began laying track, beginning with a single straight line cutting through the middle of the East Lot parking area (east of Grand Ave. and south of all of Knott’s shops and attractions) and extending north to a spot near today’s Beach Blvd undercrossing. In this initial configuration, the cars would just run back and forth on the track with no turn-around. Meanwhile, Knott’s searched for qualified gripmen and conductors to run the cars and had appropriate uniforms made for them. The cars arrived at Knott’s Berry Farm on flatbed trucks on March 17, 1955 and were immediately offloaded onto the new tracks. Rather than operating on a traction cable system as they had in San Francisco, Knott’s saved money by converting them to electrical power. Each car had a huge submarine battery added to it — the only kind of battery in that era capable of running a vehicle of that weight. |

|||

Photos from Knotty Post newsletter, April 1955, courtesy Orange County Archives Harry Davidson checking batteries’ water level and Ed Markham adjusting the battery charger |

|||

|

The batteries were recharged at the end of each shift in an area behind the petting zoo at Old McDonald’s Farm. According to Steve Knott (grandson of Walter and Cordelia), “Around 2008, the current management of the park contacted me because they’d found these mysterious pits — they looked like bunkers — while digging a foundation for a new attraction at Camp Snoopy. I told them those pits were the maintenance bays for the cable cars, where you could get under the cars to make repairs.” Upon arrival at Knott’s, the cars also underwent major cosmetic refurbishment, making them look almost new again. Within two weeks of the cars’ arrival, they were in operation and receiving positive reviews from guests. |

|||

Photo from Knotty Post newsletter, May 1955, courtesy Orange County Archives E.J. Fulsang throws the grip control — despite no actual cable to grip |

|||

|

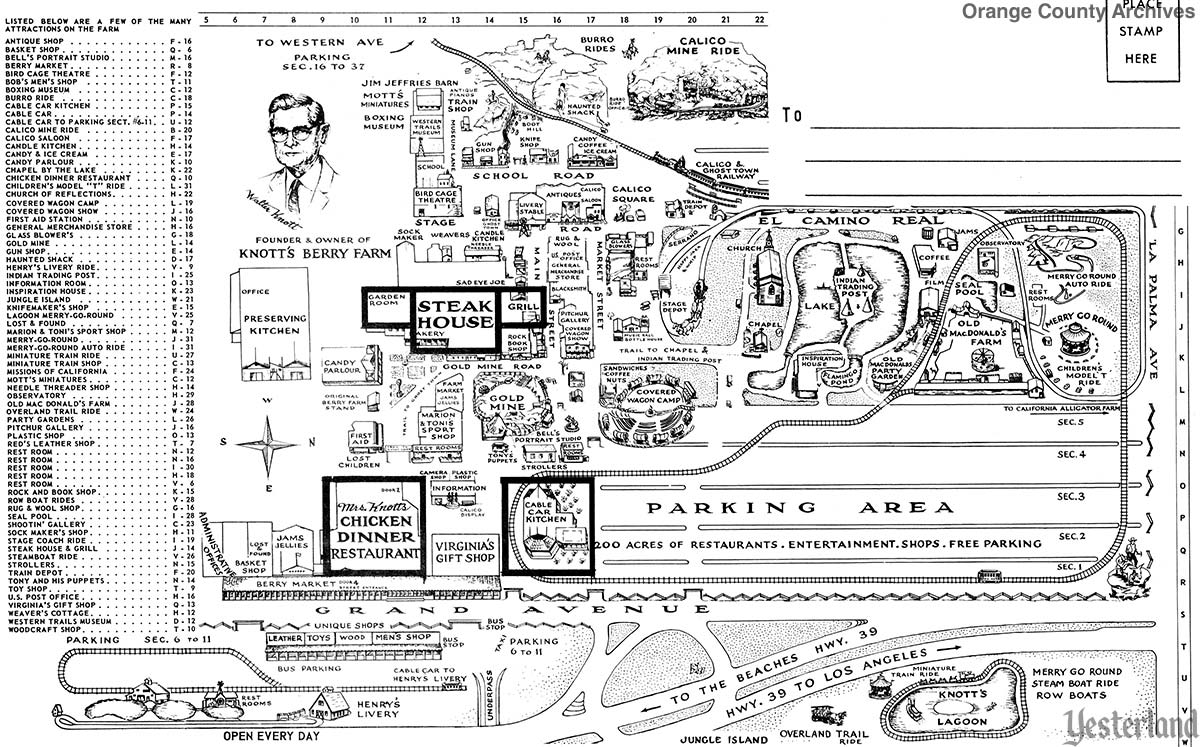

In June 1956 the farm’s Ghost Town & Calico Railroad track crew, headed by Ulysses G. Goates, extended the cable car tracks by an additional 1,500 feet, bringing the total trackage to three fourths of a mile. This new line made a wide loop around the East Lot. Most of the cars were reconfigured to run in only one direction, with controls at just one end of the car and additional passenger seating where the second set of controls had been. In 1956 or 1957, Knott’s bought two more derelict cable cars. One of these “new” old cars was #49. The other was #43, built by the W. L. Holman Co. in 1907. Knott’s did not convert #43 to one-way-only travel, and it retained both sets of controls (dual grips and brake levers), which were promptly rendered immovable by building wooden decks around them. For many years — and perhaps for its entire time at the Farm — #43 sat on a section of rail on the east side of the railroad shop near Knott’s grounds-keeping building. Likewise, said retired Knott’s employee George Sapp, “I never saw the #6 move.” It’s possible that car #6 was the one car stored specifically for spare parts in the cable car barn or railroad roundhouse. Later, the track through the East Lot was further extended to cross Grand Avenue, stopping just north of Virginia’s Gift Shop. A signal light for the cable cars can still be found at the crosswalk on Grand Ave in front of Mrs. Knott’s Chicken Dinner Restaurant. In the January 1958 issue of the farm’s Knotty Post staff newsletter, an unidentified employee described the development of new attractions along the original leg of the cable car line: “Frank and Reed, operators of the cable cars in Parking Sections 6 and 11 [a.k.a. the East Lot] report fine progress on the [Old Mill Stream] Trout Pools, also plenty of action at Henry’s Auto Livery ride. Frank and Reed are the unsung heroes of the Cable crew, but are doing a fine job caring for our guests in that area.” |

|||

Photo courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Extended rail loop for the cable cars |

|||

|

By now though, there was also a second, longer loop which ran from the cable cars’ hub near Virginia’s Gift Shop, north to La Palma Ave, then west along La Palma, then stair-stepping south and east, encircling all the North Parking Lot and the animal-related attractions that would later be replaced by Fiesta Village and Camp Snoopy. This line then returned to the hub near Virginia’s Gift Shop. In the aforementioned 1958 article, the employee also wrote about this new loop and the many attractions to which it provided easy access: “The Cable Car Crew would like all to know we have now taken our proper place on the Farm. We are very proud of our new restaurant [probably in the “El Camino Real” area] and Mission Trails Market. These, added to the Merry-go-round, Seal Pool, [Old] MacDonald’s Farm, the Observatory, and our Film Shop, make this stop very entertaining, as well as educational.” Passengers on this new North Lot line likely would have also seen California Mission models, meandering animals, and colorful Old West characters like a prospector and his burro, or a bandit robbing a stagecoach. |

|||

Photo, 1959, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Naming contest for what would become Cable Car Kitchen |

|||

|

In late 1958, construction began on a restaurant at the cable cars’ hub. Its working title was Jester’s Kitchen. But Andy Anderson — husband of Walter Knott’s youngest daughter, Marion — put an ad in the local newspapers announcing a contest to give the restaurant a permanent name. The winner, out of more than 15,000 entries, dubbed it the Cable Car Kitchen after its proximity to the cable car line. The restaurant opened just in time for Summer 1959, right next to newly expanded cable car track. At about this point, the cable cars were also turned to run in the opposite direction of the way they’d been traveling. |

|||

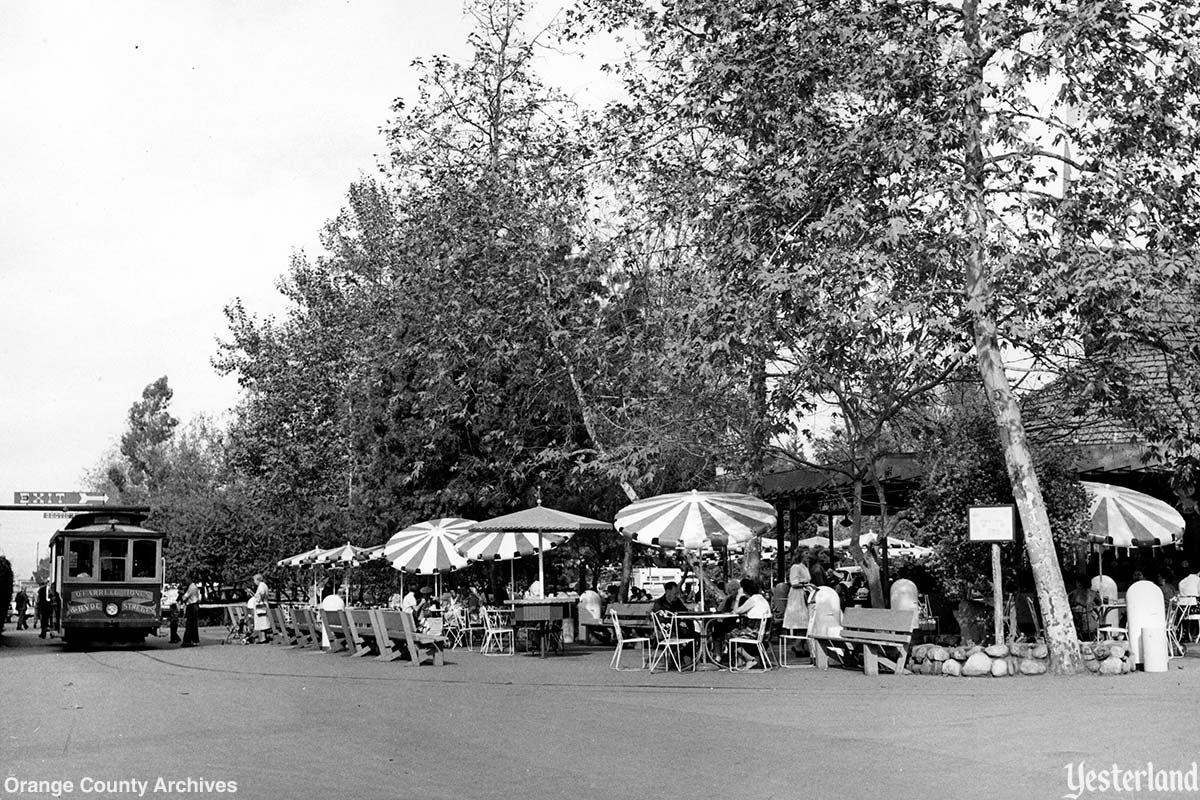

Photo, 1970s, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Doing double-duty as an attraction and a parking lot tram |

|||

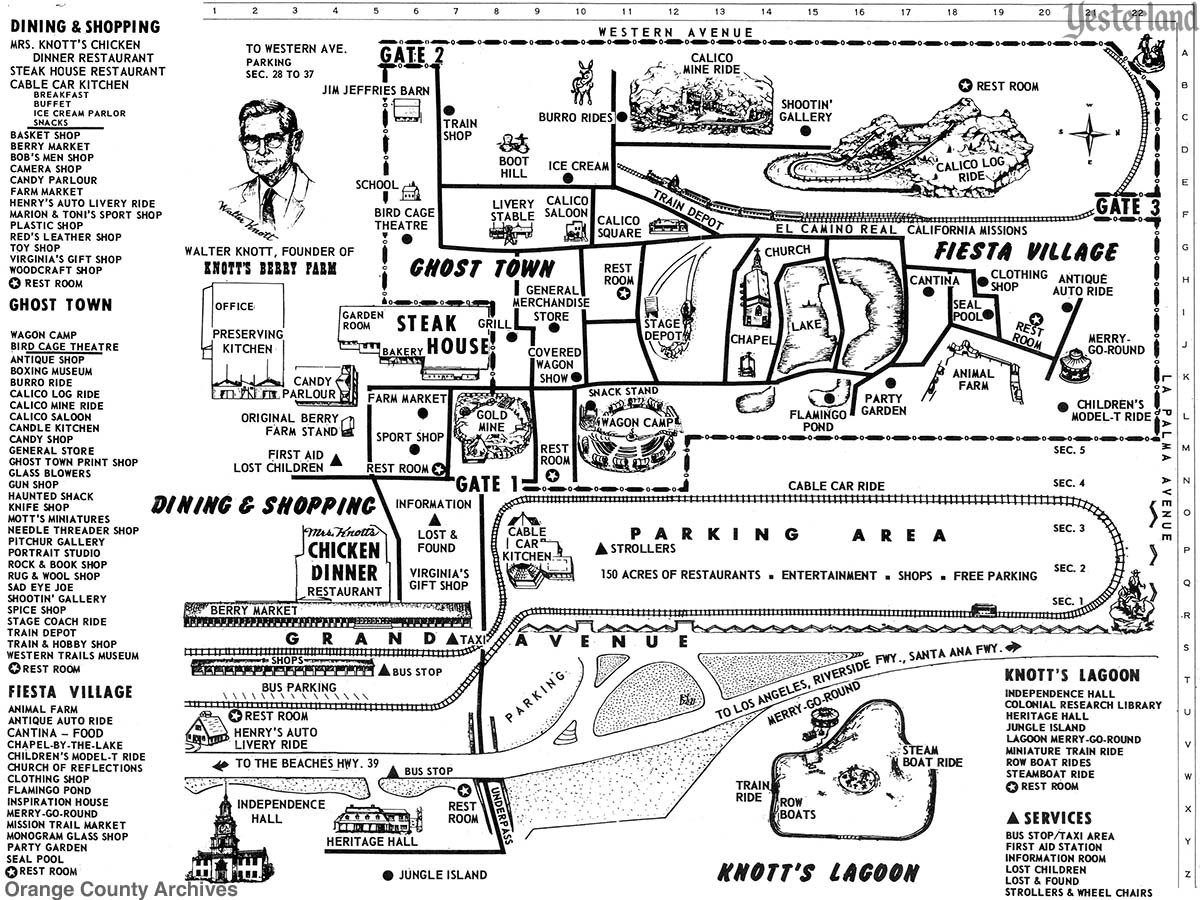

1965 mailable map, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Map (not to scale) showing two tracks: East Lot (bottom left) and North Lot (large loop) |

|||

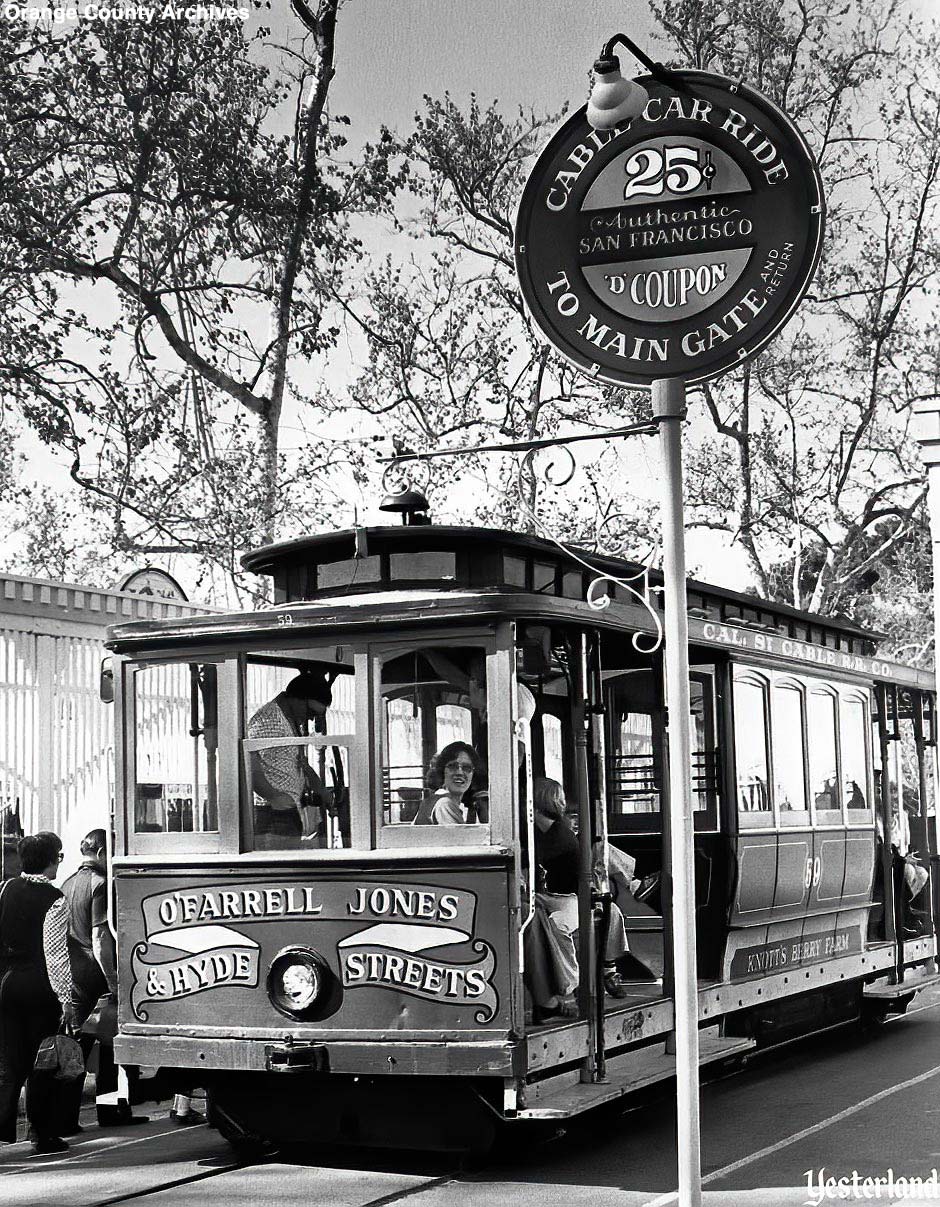

Photo, 1970s, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection 25 cents or “D” Coupon |

|||

|

“When I was young, I rode the [east] parking lot shuttle cable car a number of times because it was a free ride,” said former Orange County resident and Yesterland.com curator Werner Weiss. “I don’t think I ever rode the longer north parking lot cable car loop because it required cash payment or a ticket from a Knott’s ticket book.” |

|||

Map circa 1972, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Combined loop track, which remained outside the gated theme park portion of Knott’s. |

|||

|

A 1972 map of the Farm shows the route through the East Lot even further altered, now returning to the entrance area by coming straight up Grand Avenue in front of the Chicken Dinner Restaurant, the Berry Market, and other shops. |

|||

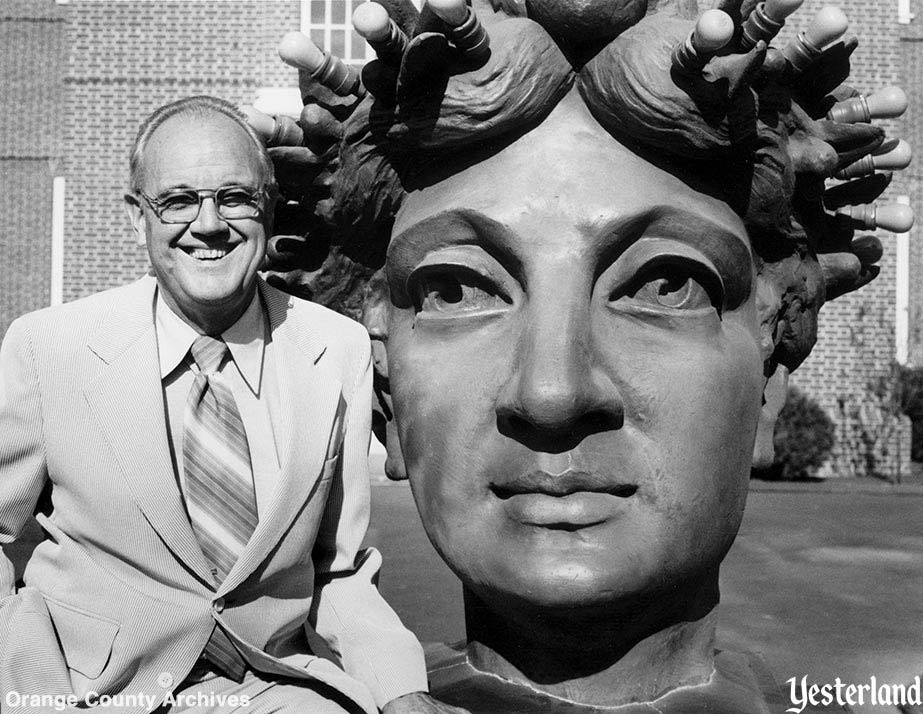

Photo courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Russell Knott and the “Goddess of Progress” |

|||

|

Soon thereafter, Knott’s Berry Farm’s role in the marginalia of San Francisco history expanded even further. William Roddy, public services director under San Francisco Mayor Joseph L. Alioto, was on the hunt for a particular historical artifact that had long-since gone missing. A 22-foot-tall statue of the “Goddess of Progress,” sculpted by artist Francis Marion Wells and cast in 1894, had once stood atop the dome of San Francisco’s stately City Hall and had toppled to the ground during the great earthquake and fire of 1906. In fact, it’s likely that the only artifact saved from the old City Hall was the head of that statue. The head was 48-inches tall, 700-pounds, and its brow was studded with a crown of lightbulbs. Roddy learned that the head had passed through a number of owners over the years but had been stored in a city warehouse for at least five years until the mid-to-late 1950s. It turned out Knott’s Berry Farm had purchased the head at the same time it purchased some of its cable cars. Knott’s had still not found a use for the head, didn’t know its origins, and had stored it in their own warehouse for almost twenty years. Roddy called Russell Knott (Walter and Cordelia’s son) and asked for the head’s return. Russell told him that the Knott family had only just recently found a use for the giant head and planned to place it at the entrance to the Roaring ‘20s section of the park which was then under development. In November 1974, Russell begrudgingly agreed to give the head back to the city by January 1, 1976, on the condition that San Francisco’s mayor and county officials agree to accept the gift in person. Indeed, the return of the long-lost noggin was celebrated on the anniversary of the earthquake — April 18, 1976 — with an event at the rotunda of City Hall featuring Mayor Alioto, a bevy of officials, media, and a Dixieland band. Around this time, the cable cars themselves began to be edged out at Knott’s Berry Farm. A map of the park dated June 1975 shows the cable car track abbreviated to just about half of its old northern loop, only circling the “North Lot” that would eventually become Camp Snoopy. By late 1976, the cable cars no longer appeared on Knott’s official maps at all, but the line was half-heartedly maintained. It was trimmed again in 1978 and the “shop” for the cable cars was removed with the construction of the Montezooma’s Revenge roller coaster. Sapp recalls the old shop as “pretty nice and functional. It had a lot of character.” The shop’s replacement, located way “out towards Beach Blvd near Henry’s Auto Livery, was like Siberia.” By then, Knott’s estimated that twelve million people had ridden the cable cars on their property. But the cars had not been without their problems. “We enjoyed having them,” recalled Steve Knott, “but they often tangled with cars driving through the parking lots.” |

|||

Photo, 1964, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Cable Car track work adjacent to the Cable Car Kitchen restaurant |

|||

Photo courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection Not quite like being in San Francisco |

|||

|

Most of Knott’s cable cars were mothballed in early 1979. Near the end of that year, the Knott family offered to give both the cable cars and the Ghost Town & Calico Railway to Bud Hurlbut to operate. Hurlbut had designed, built, owned and operated both the Calico Mine Ride and the Timber Mountain Log Ride — the farm’s two signature themed attractions — and also owned and operated almost all of the other rides on the property outside the Roaring ’20s area. Hurlbut declined the offer, likely because the cable cars and railroad generated very little revenue at that time. At that point, Knott’s made plans to phase out the cable cars entirely. In January 1980, a Bay Area citizens’ group called Save the Cable Car contacted Knott’s Berry Farm, asking if they would donate their cars back to the city. It appears the City of San Francisco was game to re-launch of their dormant cable car system, but only had a shoestring budget for doing so. “They virtually begged us for the cable cars,” recalls Steve Knott. “They wanted to rebuild their cable car system, but they’d given most of it away over the years. They wanted those cars so badly.” |

|||

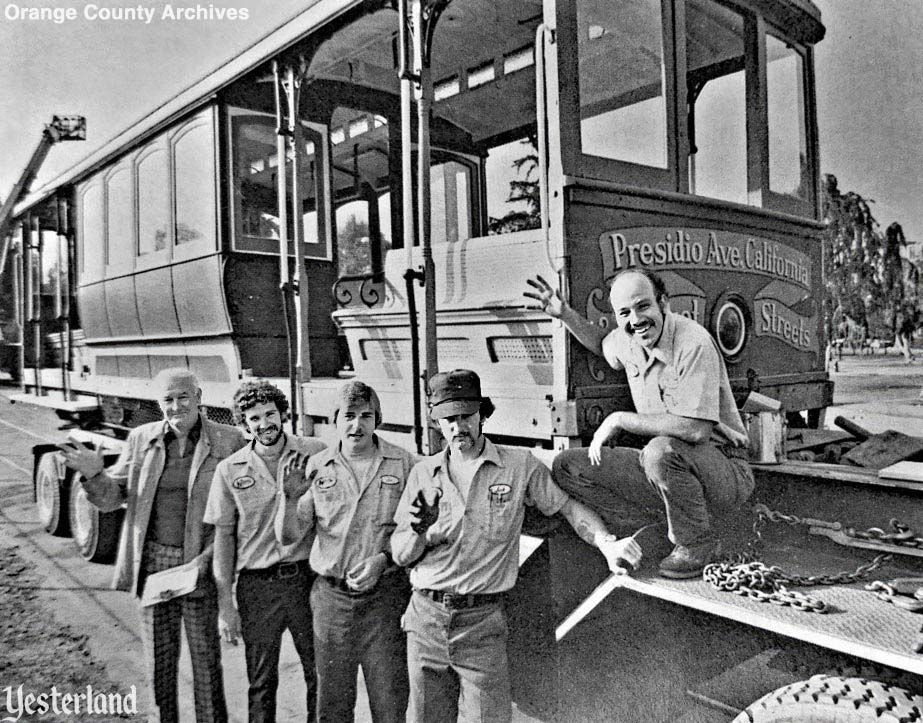

Photo from Knotty Post newsletter, Nov. 14, 1980, courtesy Orange County Archives Preparing to ship back to San Francisco |

|||

|

In October 1980, Knott’s decided to donate back four of the six cars they’d purchased to the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). There were a variety of reasons for the end of the cable cars’ time at from Knott’s. It probably began in 1968 when Knott’s put a gate up around their amusement park area and began to charge admission. This curtailed the cable cars’ ability to bring people from the parking lots directly into the heart of the park, and vice versa. And by 1980, Knott’s was making plans to develop Camp Snoopy (opened 1983) in what had been one of the main parking areas served by the cable cars. |

|||

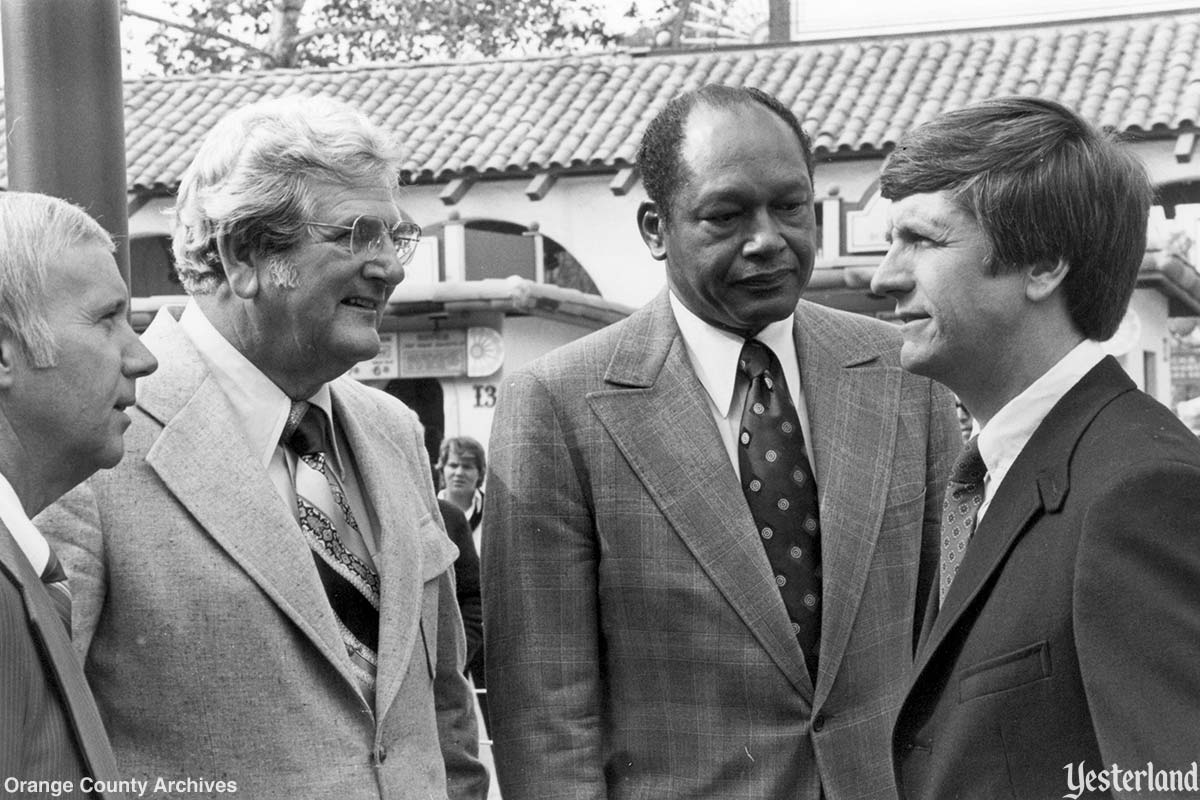

Photo, 1980, courtesy Orange County Archives, from the Knott’s Berry Farm Collection (L to R) Mayor Les Reese, Supervisor Ralph B. Clark, Mayor Tom Bradley, and Knott’s Don Oliphant. |

|||

|

Three cable cars were delivered back to San Francisco in mid-October 1980 to little fanfare. A fourth car was sent in early November after a ceremony at the park’s main entrance, involving can-can dancers, a fake gunfight, and the playing of “I Left My Heart in San Francisco” by Knott’s Townsfolk Country Band as the car made its last run around the tracks. Those attending included the Knott family, Buena Park Mayor Les Reese, Orange County Supervisor Ralph B. Clark, and (somewhat inexplicably) Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley. At the end of the ceremony, the cable car was loaded onto a truck bound for San Francisco. A banner was placed on the back of the car, reading “From Knott’s Berry Farm to San Francisco or Bust!” Upon the cars’ return, the truck stopped in front of San Francisco City Hall, where Don Oliphant — another of Walter Knott’s son-in-laws — presented Mayor Dianne Feinstein with the deeds to the cars along with signed resolutions from Mayors Bradley and Reese and Supervisor Clark. Feinstein reciprocated with a Proclamation of Appreciation, declaring November 19th to be official “Knott’s Berry Farm Day” in San Francisco. About $20,000 in modifications were supposedly needed to get the cars ready to go back into service on city streets. At least some of the cars were earmarked for possible use on the California-Hyde line and the O’Farrell, Jones & Hyde line. Instead, SFMTA soon resold all four cars. SFMTA sold car #6 to a company called Classic Cable Car Charters, located in Healdsburg, California. In the early 1990s this company used the car as a template to build new “motorized cable cars” for a San Francisco tour company. Unfortunately, they left car #6 outside where it eventually succumbed to the elements. Car #20 was sold by SFMTA to a now-unknown buyer. It may still be out there somewhere. The other two cars sold by SFMTA — #49 and #59 — ended up at the Oakwood Senior Care retirement home in Auburn, California. Car #49 (built in 1912) was later purchased from Oakwood on Craigslist by Brett Folena of Auburn. As of 2019, it was still sitting in Folena’s front yard. Car #59 is still at the retirement home. Knott’s initially thought they would retain their two remaining cable cars, keeping one “activated” or displayed on their property with the other in storage as backup. But soon the decision was made to unload those cars as well. In 1981, Knott’s sold the first of their remaining cars, #17, to the City of San Diego’s Gaslamp Trolley Project. Knott’s suggested #17 to them specifically because it had been the best and fastest car in their fleet. However, the car was configured for 42-inch rail and the Gas Lamp District had already installed 48-inch rail. The car sat dormant in a Metropolitan Transit Development Board maintenance yard for years until 1997 when Poway-Midland Railroad (PMRR) president John Ohler learned that the yard was slated to be redeveloped. The PMRR is a heritage railroad that runs through Old Poway Park in Poway, California. Ohler asked for the cable car and the City of San Diego happily obliged. The car was delivered to the park on Oct. 30, 1997, was restored by volunteers, and now carries passengers again. The other car remaining at Knott’s, #43, was sold or given to the Southern California Railway Museum in Perris, California. Knott’s made fewer modifications to #43 than most of the other cars and barely used it (if at all), undoubtedly making it particularly appealing to the museum. |

|||

Photo by Chris Bales, 2014 Vintage San Francisco signal, still in place on Grand Avenue |

|||

Photo by Chris Bales, 2014 Another vintage San Francisco signal on Grand Avenue |

|||

Photo by Chris Bales, 2014 Cable Car Kitchen when it reopened in 2014 |

|||

|

At Knott’s Berry Farm, a few reminders of the cable cars linger on. One of a number of old traffic signals that may have been purchased along with the cable cars remains on Grand Avenue near Mrs. Knott’s Chicken Dinner Restaurant. Also, the Cable Car Kitchen still stands and, after several name changes over the years, is again called the Cable Car Kitchen. But to ride an authentic cable car one must now go to Poway, or Perris, or of course to San Francisco, where in 1984 they revived their historic cable car system despite letting the six Knott’s Berry Farm cars slip away again. |

|||

Photo by Werner Weiss, 2018 Cable Car #59 in San Francisco in 2018 — but not the same #59 that was at Knott’s |

|||

|

Author’s note: Thanks to Steve Knott, George Sapp, and Sergio Gonzalez for sharing their memories; to Paul Bignardi of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency for sharing his encyclopedic knowledge of cable cars; and to Stephanie George, Werner Weiss and Ken Stack for their editing help. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

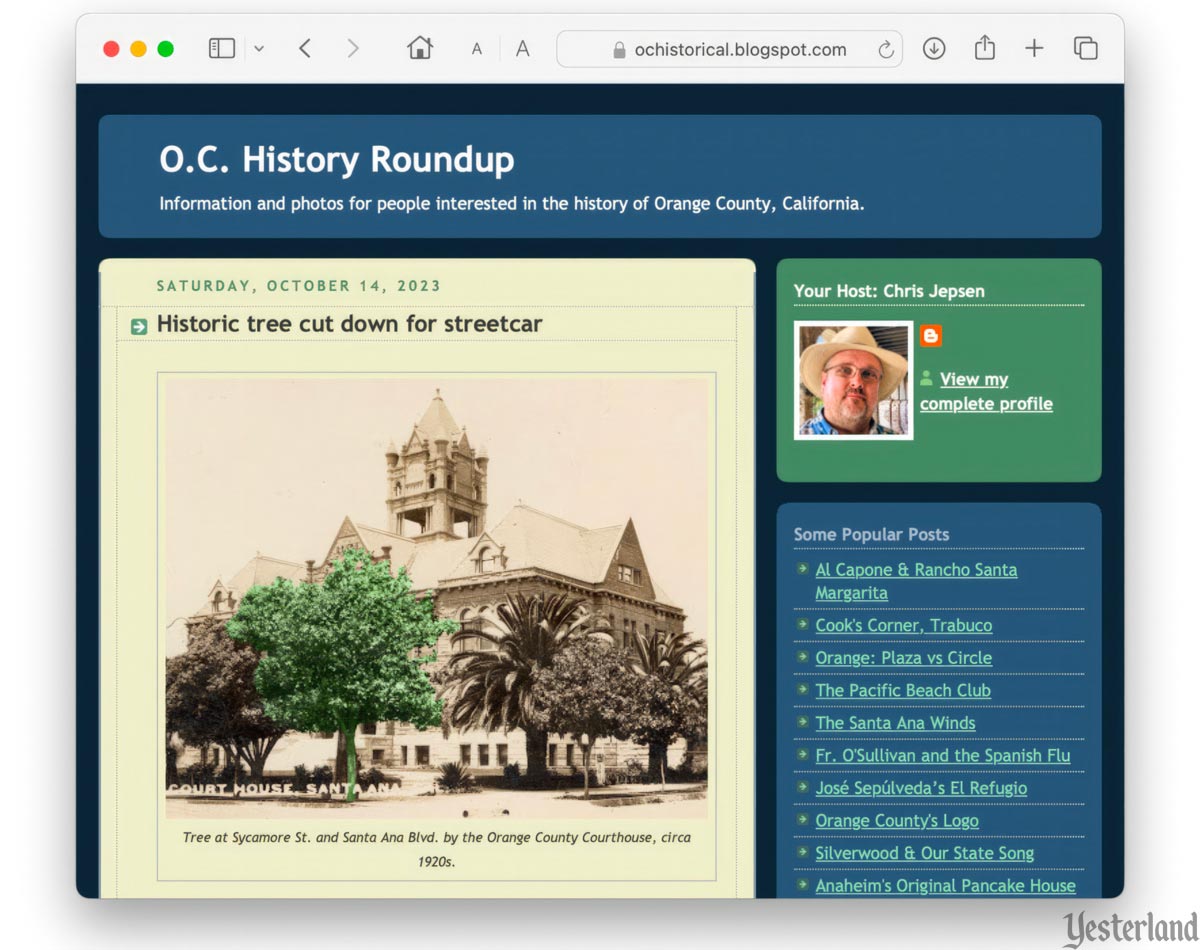

About Chris Jepsen Chris Jepsen is a local historian in Orange County, California. He is president of the Orange County Historical Society. Chris blogs about Orange County history at the O.C. History Roundup. |

|||

screen capture O.C. History Roundup by Chris Jepsen [opens new window] |

|||

|

|

Click here to post comments at MiceChat about this article.

© 2023 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated November 10, 2023 |

||