|

|||

|

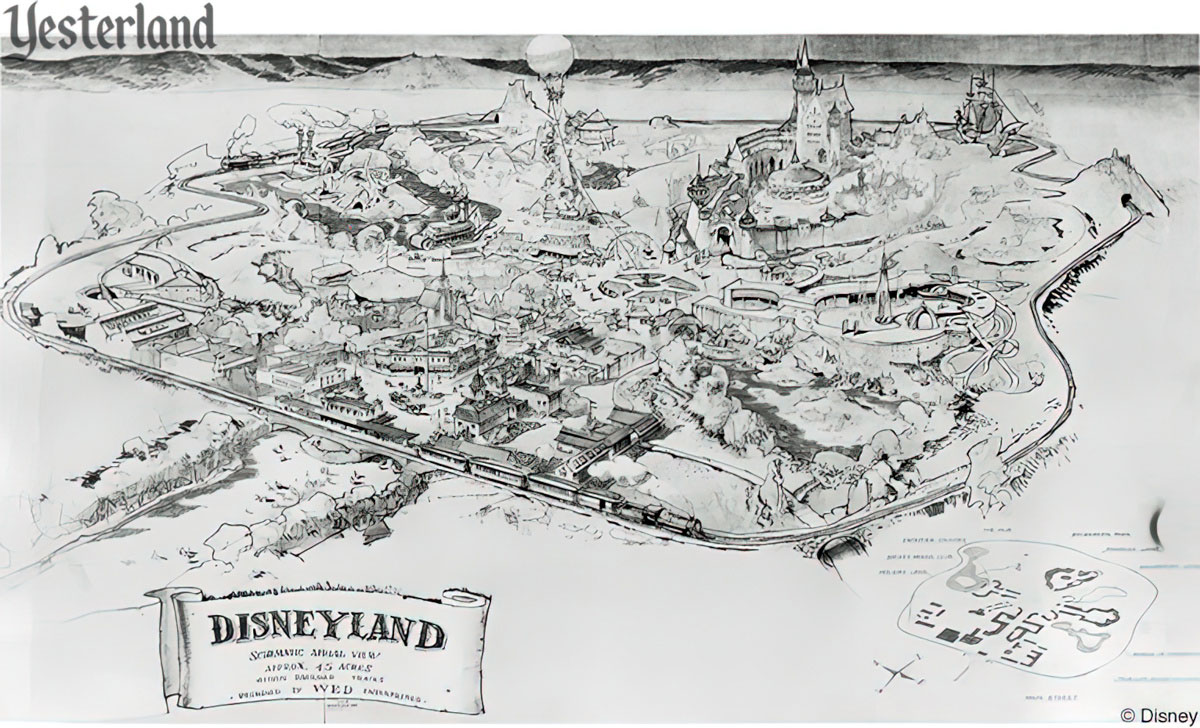

I never get tired of the “lost weekend” story. I’ve read it and heard it told many times. The details change a bit, especially the dialog. (Nobody was there with a tape recorder.) But there’s no doubt that it happened. We can still enjoy the results of that weekend—the wonderful drawing reproduced in this article and, more importantly, the fact that Walt and Roy Disney were able to scrape together financing for Disneyland.

Adapted from a Yesterland article published February 19, 2014 |

|||

drawing by Herb Ryman, 1953, copyright Disney |

|||

|

The story begins September 26, 1953. Less than a year earlier, Walt Disney set up a new company, WED Enterprises, intending to make his dream of a new kind of amusement park a reality. Walt had assembled a small group, which included hiring a 20th Century Fox art director, Richard “Dick” Irvine, who had worked for Walt in the past. By now, WED was running out of money. Biographer Neal Gabler describes a life-changing phone call in Walt Disney: The Triumph of American Imagination (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2006): Herb Ryman, an art director who had worked at the studio in the story department in the 1940s before Leaving for Twentieth Century-Fox, was painting at his home on the morning of September 26, when he received a call from an old colleague, Dick Irvine. Irvine told him that he was at the studio with Walt and Walt wanted to have a word with him. As Ryman later related it, Walt got on the phone and asked him how long it would take for him to get to the studio. Ryman said fifteen minutes if he came as he was, a half-hour if he dressed. Walt told him to come as he was and Walt would meet him at the studio gate. |

|||

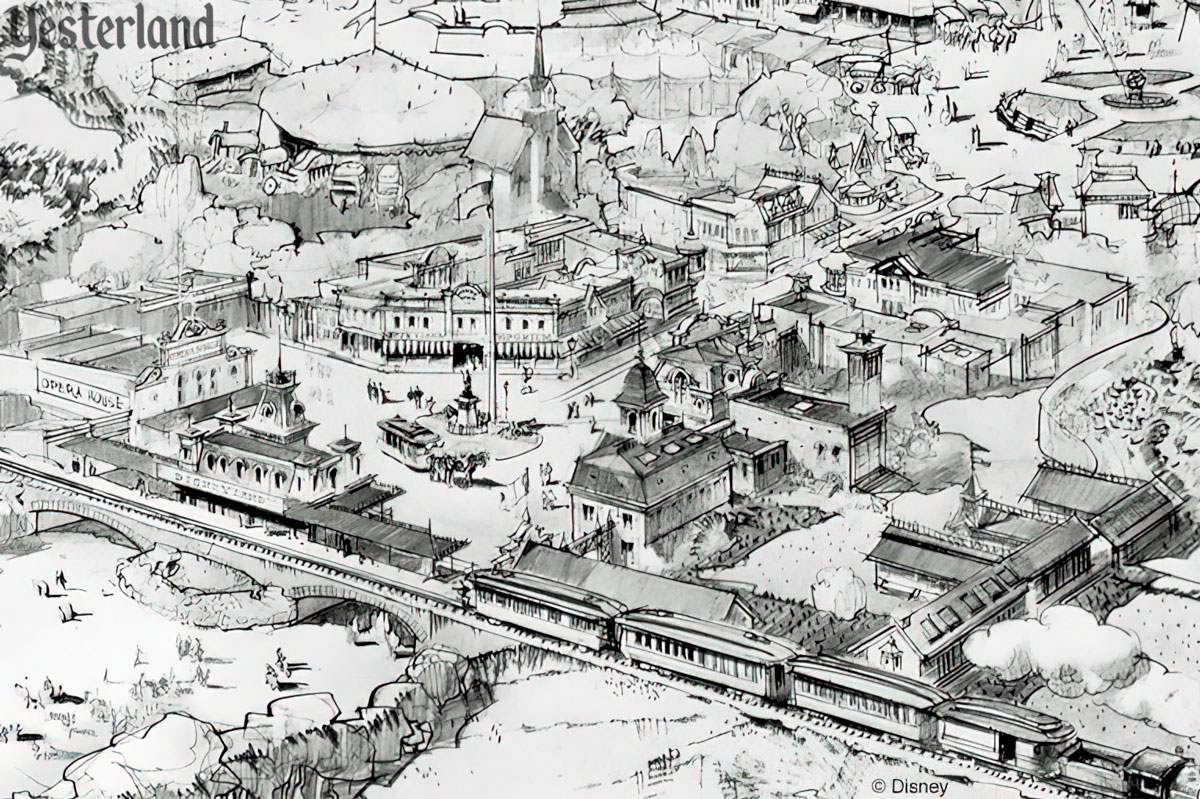

detail from drawing by Herb Ryman, 1953, copyright Disney Main Street detail |

|||

|

In Walt Disney: An American Original (Simon and Schuster, New York, 1976), biographer Bob Thomas has this account of the conversation that happened after Ryman arrived: Walt greeted him affably and told him, “Herbie, we’re going to build an amusement park.” “That’s interesting,” Ryman replied. “Where are you going to build it?” “Well, we were going to do it across the street, but now it’s gotten too big. We’re going to look for a place.” “What are you going to call it?” “Disneyland.” “That’s as good as anything.” “Look, Herbie, my brother Roy is going to New York Monday to line up financing for the park. I’ve got to give him plans of what we’re going to do. Those businessmen don’t listen to talk, you know; you’ve got to show them what you’re going to do.” “Well, where is the drawing? I’d like to see it.” “You’re going to make it.” Here is Ryman’s reaction from Walt Disney’s Railroad Story (Pentrex, Pasadena, 1997) by historian Michael Broggie: “No, I’m not,” was Herb’s emphatic response. “This is the first I ever heard about this. You’d better forget it. It’ll embarrass both you and me. I’m not going to make a fool of either one of us.” |

|||

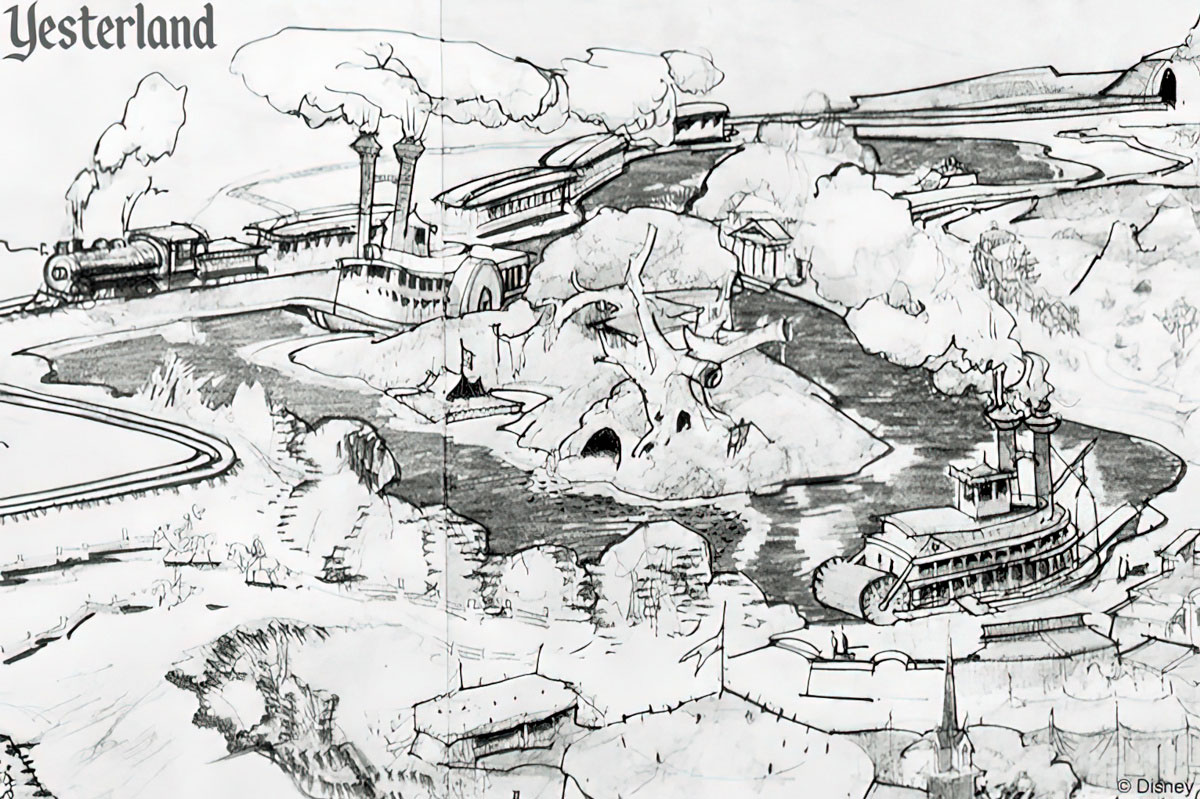

detail from drawing by Herb Ryman, 1953, copyright Disney Frontier Country detail |

|||

|

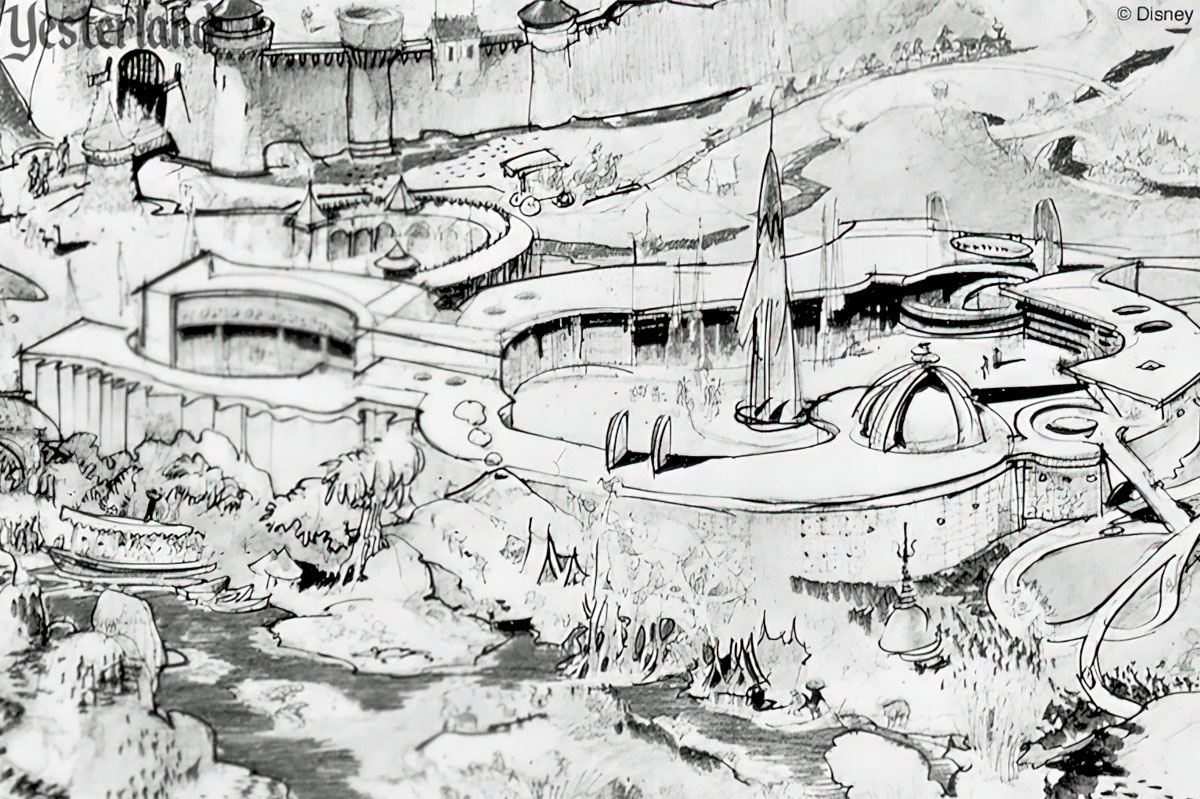

According to Broggie, Walt Disney eventually won over Ryman: “Herbie, this is my dream. I’ve wanted this for years and I need your help,” [Walt] pleaded. “You’re the only one who can do it. I’ll stay here with you and we’ll do it together.” Convinced and moved by Walt’s unusual, emotional display of sincerity, Herbie agreed. Soon, he created a few quick conceptual sketches of the project, aided not only by the drawings and plans of Marvin Davis and Dick Irvine, but also Walt’s verbal descriptions. With each themed section, Walt carefully crafted—in precise detail—how it would work, mentally walking through every area and building, and riding on every attraction. His storytelling ability wove word pictures, from which Herb quick-sketched visual interpretations with a carbon pencil. For the next 42 hours, the two spent all of their imaginative and creative energy in a marathon session. Early Monday morning, Marvin Davis and Dick Irvine walked into the littered room. They found a bedraggled Walt and a bone-weary Herbie sitting there, looking at a large Vellum panel, illustrated in pen, with a bird’s-eye view of a completely detailed theme park. In the lower left corner, a scroll proclaimed “Disneyland—schematic aerial view—approximately 45 acres within railroad tracks—designed by WED Enterprises.” In Ryman’s drawing, Disneyland is recognizable, although different from what opened to the public on July 18, 1955. The named parts of the park are Main Street, The Hub, Holiday Land, Frontier Country, Mickey Mouse Club, Recreation Park, Fantasy Land, Lilliputian Land, and True-Life Adventureland. |

|||

detail from drawing by Herb Ryman, 1953, copyright Disney World of Tomorrow detail |

|||

|

The drawing was an amazing accomplishment—by someone who was not even an employee of Walt Disney at the time. Ryman’s employment status quickly changed. Herb Ryman continued to design for Disney theme parks. His renderings of Sleeping Beauty Castle, Cinderella Castle, and New Orleans Square are legendary. Although he retired from Disney in 1971, he produced conceptual drawings for EPCOT Center, Tokyo Disneyland, and Disneyland Paris as a consultant. In 1989, Herb Ryman died—and the Ryman-Carroll Foundation was born. To see what this organization does, visit the Ryman Arts website. |

|||

|

|

|||

| Click here to post comments at MiceChat about this article. | |||

|

|

© 2022 Werner Weiss — Disclaimers, Copyright, and Trademarks Updated Sep. 28, 2022 Thank you to John Delmont for the excellent scan of the Herb Ryman drawing. |

||